On July 25th, 2018, an angry Canadian took to the blogosphere to rant about the state of the field of neurology, and how they are too foolish to notice one of the most important advancements in human evolution to date, writing:

We know they share thoughts without speaking, conspire nonverbally to commit practical jokes for example (although not in complete silence; apparently a fair amount of giggling is involved). The twins call it “talking in our heads”. Back in 2013 one of their neurologists opined that “they haven’t yet shown us” whether they share thoughts as well as sensory experience, but neurons fire the same way whether they’re transmitting sensation or abstraction; given all the behavioral evidence I’d say the onus is on the naysayers to prove that thoughts aren’t being transmitted.

The twins in question, at focus in this rant, were the conjoined Krista and Tatiana Hogan. Conjoined at the head, specifically, and in such a way that they could actually communicate with each other nonverbally. The writer was obsessed about the intricacies involved with this deeply unsettling happenstance product of random chance. He goes on:

Eleven years after the birth of the most neurologically remarkable, philosophically mind-blowing, transhumanistically-relevant being on the planet, we have nothing but pop-sci puff pieces and squishy documentaries to show for it. Are we really supposed to believe that in over a decade no one has done the studies, collected the data, gained any insights about literal brain-to-brain communication, beyond these fuzzy generalities?

I for one don’t buy that for a second. These neuroscientists smiling at us from the screen— Douglas Cochrane, Juliette Hukin— they know what they’ve got.

If you’re curious, the writer of the blog is little-known biologist and occasional science fiction writer, Peter Watts. What set him off was reading the twins talk to each other as separate people, despite being linked by a thalamic bridge. This mutation allows the conjoined twin’s brains to communicate with each other while retaining two unique personalities. Peter is angry because no one seems to get it: The girls are a living biological internet. A hive mind. And Peter is very jealous he can’t study her himself.

In all the world of science fiction, I’ve never encountered a more odd-ball writer as Mr Watts. He’s my closely guarded guilty pleasure. He’s erratic, sometimes juvenile, but past that he’s brilliant in his writing. Oh, also, he’s banned from the United States. Back in 2009, Mr Watts punched a border agent for seemingly no reason. Peter’s as insane in reality as he is in his books.

Constrained to live out his days in the hellscape of Truckistan, his blog is a perpetual wellspring of philosophy and entertainment. Just look at that title:

His blog is a priceless gem I return to every few months where he jots down the frantic and frenzied concoctions of his mind when he’s not doing Marine Biology or Science Fiction writing. He doesn’t publish full length books often, but when he does he imbues it with all the madness of his blog. It’s something of an appetizer.

For today’s post, I want to bring you into his main series: Rifters. A series that predates other existential dread pieces like Three Body, To Walk the Night, and various Lovecraft works. Concepts akin to Liu Cixin’s Dark Froest are brought up in an almost prototype way before more recent authors formalized the concepts. And the world of Rifters is grim. It’s something of a cross between an Al Gore nightmare and Evola’s spiritual treatise. Earth’s governing bodies operate behind clandestine operations ran from facilities on the moon and orbital stations dotting Earth’s sphere of influence. The solar system is host to small selective utopian delusions that occasionally burn down in similar pattern to Earth’s own collapsing ecosystem. Earth itself is described in the books as “A plane crashing, pilots putting on the parachutes”, to paraphrase. The Americas are ruled by the reactionary WestHem government, with the clandestine Panopticon setting its national and planetary policies. Most of Asia is either submitting to or resisting something called the Moksha Mind, a hive mind exploring realms of thought beyond mortals. The UK is an archipelago of artificial islands to manage its grotesquely oversized population. Most of the equatorial regions are fraught battlefields between Moksha and WestHem, with desperate third worlders etching out an existence in the valley of tears they leave behind. What’s left of the various nation states bicker with the rest. Most of the planet’s inhabitants are either subsumed into a hivemind, plugged into a VR reality, or - for a select few - enjoying life in a tight Biomedical Security Apparatus plagued by bioterrorism and natural disasters. WestHem also tolerates various cults and communes dependent on it for security, eagerly exploring the technology of divergent minds. In essence, WestHem lives off of weaponized autism. Soldiers even have the choice to use implants that deactivate their consciousness for their tours of duty - something equated with a cheap form of time travel, for those hoping to wake up in a few years when the world is better. Humanity has even started resurrecting extinct hominids to make up for stalled birth rates and declining IQ. It’s speculated at one point that the population of the Earth now had more humans in an unconscious state than a conscious state. And it’s that terrifying reality that stalks the pages of any good Rifters book.

Not all is doomed though. Near the sun, a great space station uses solar fusion - still impossible on Earth - to produce a stream of antimatter particles which it beams to various planets. Starships enter these antimatter streams and effectively sail to any destination they desire without need for fuel. And who knows, maybe some of the utopias in space may stabilize and become proper colonies?

In 2006, Peter released the newest addition to his Rifters series: A first contact story, where the denizens of the Solar System encounter something from beyond. Titled Blindsight, it is a double, perhaps triple entendre in typical Watts fashion.

Blindsight, if you are unaware, is a rare form of brain damage. The conscious mind’s access to visual data is severed from some severe injury, but the nerves which carry the information can still reach the older parts of the brain - the subconscious and reptilian parts. The conscious mind cannot see, but the instinctual subconscious can. One of the peculiar symptoms of this condition is that if you were to throw something at someone suffering with blindsight, they would reflexively reach out to grab it. Then, they would stand confused how they knew something was being thrown at them at all. Blindsight patients often come to realize that there is something of two personas within them. Themselves, the conscious mind not able to access visual information. The second being, their unconscious minds which they must find new negotiations with to sense the visual data at a distance. People with Blindsight know the terrifying truth of conscious beings: We are not the entirety of our brain. We, the conscious being, exist at the peripheral of the brain. The vast majority of the brain is an inaccessible world our conscious minds prod at with neurological columns. The sea of unconsciousness is deep, and much of Peter’s writing delves into just how deep that sea is. His approach is to make you question your flesh as much as you question the cosmos. It’s with the example of Blindsight that Peter reveals a soft truth: life does not need consciousness and, at least for how it evolved in humanity, life may even be disadvantaged from it in some contexts. Life may have a natural selection pressure trying to get the lump of brain that constitutes the conscious mind off it like a tumor it would be better off without. And with that foot in the door, Peter Watts brings you in wanting to learn more.

Blindsight has several theme:

The first and primary question of Blindsight is if consciousness is actually a permanent feature of the human species. Much like the embryonic tails we retain through our fetal lives, only to lose before we are born, how do we know consciousness doesn’t phase out? Can we be sure consciousness is a net positive in the urban digitalized world of tomorrow, when it developed for a rural hunter-gatherer context?

Another theme is identity, and how much can you lose of yourself while still retaining your soul? Many of the characters of the Rifters series are modified, genetically and mechanically. This theme, calling back to the Ship of Theseus, continues throughout.

A subtle theme of the text is also that of game theory in terms of its cosmological perspective. Here, many parallels can be drawn to Dark Forest theory in Three Body Problem. Rifters came out many years prior, but explored the cosmos not as a threat to be feared, but as a machine hostile to consciousness.

These themes start getting laid out very quickly, and you’ll have to do some heavy lifting as a reader to get through the dense hard sci-fi concepts. But after, things get lighter.

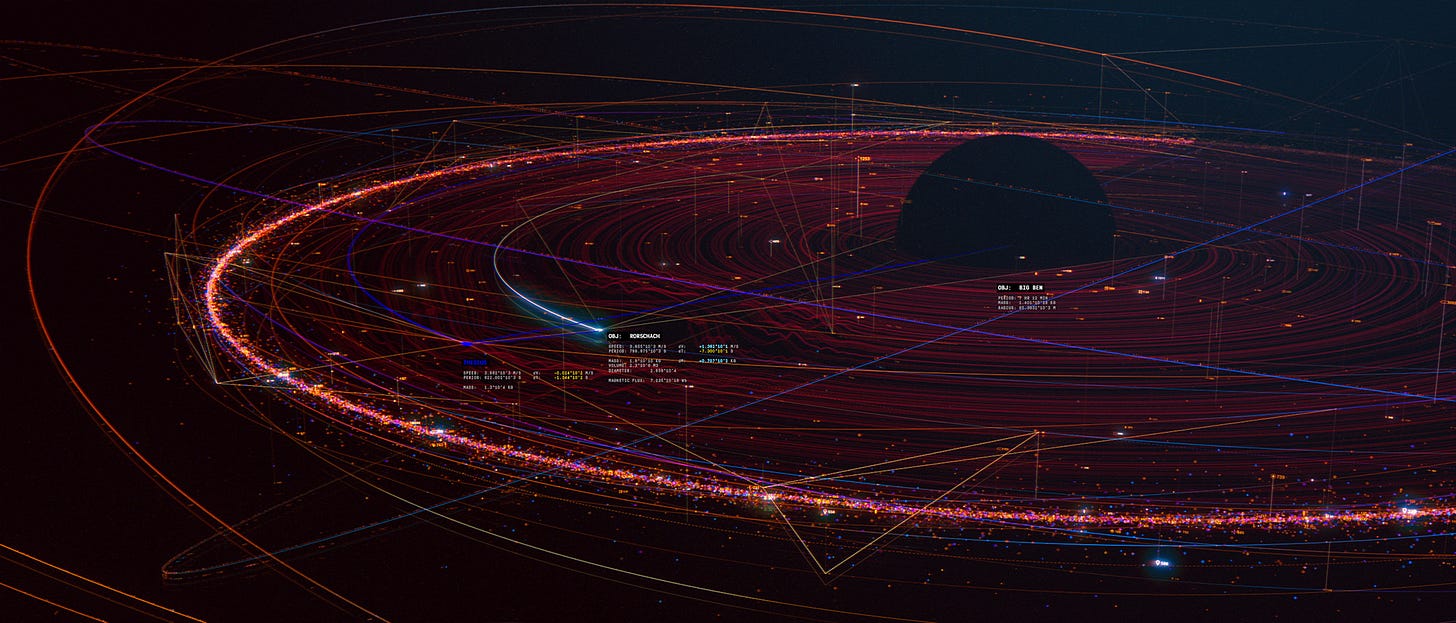

Peter’s fans make some of the most amazing art

The first thing we learn about Blindsight is that we are on a ship called Theseus, and the ship has a rich cast of characters, each described in their introductory moments. Our main protagonist and narrator is Seri Keeton. “The man with half a brain”. The other half is a computer designed to assist what’s left of his biological mind. The captain is an AI no one can talk to except the commander. The commander is one of those ressurected hominids I mentioned. Homo vampiris. And as the name might imply, yes he is a vampire. Vampires and other ghouls are real in the world of Rifters - or at least something of a biological reality of them is real. This is a bit of creative speculation from Peter, and where he shines as a biology specialist in his writing. Vampires drink blood because they are dependent on blood proteins they cannot make. Clever… Next up, the ship’s combat specialist is some kind of mix between Neanderthal and cyborg. She’s fought in many campaigns for WestHem and has a specialist for drone warfare, and I do hope you appreciate Peter wrote this when drone warfare was still a rather new thing to the public. He has a lot of innovative ideas about it. The next Crew member we’re introduced to is Susan James, also known as “The Gang”. She’s the linguist, but she also has multiple personalities. In the world of Rifters, most mental illness has been integrated into a technological management. People with multiple personalities quite literally partition their minds like we do to hard drives, allowing for distinct itemized personas to run efficiently with limited hardware. Another bit of creative thinking by Peter. Lastly, there’s the Doctor. An augmented creature in love with one of Susan Jame’s personalities. Only one, mind you. Anything else would be cheating.

If you are a reader who notices little things, very quickly you would have realized there are no humans on this first contact journey - at least, no full humans. Indeed, we eventually learn all the crew have been genetically modified as well, to allow for hibernation. But, and this is speculation, I’ve always interpreted this as WestHem’s experience with bioterrorism at work. Whatever aliens are out there, WestHem likely doesn’t want them to have a full picture of the human genome.

There is also a rather disturbing moment when our hero, Keeton, wakes up. He sees in the back rooms the hibernation beds of an entirely secondary crew. Every one of these characters is replaceable. And yes, this is likely to do with the ship’s name. Peter can be cliché at times.

You may have noticed everyone on this ship has a job to do as well. The Vampire is commanding, the Neanderthal is doing combat. The Linguist and the Doctor serve the mission. Why is Keeton here? Well that’s another dynamic introduced as we meet our crew: Keeton is a political commissar. His job is to send reports back to WestHem. Officially, this job is known as “Synthesist”, but his role is nothing more than ensuring WestHem’s policies are observed. He’s the son of an officer too. A dynasty of boot lickers. In many ways, Keeton himself comes to realize his own existence is a selective pressure against humanity’s independent and conscious thought.

These introductions increasingly hinted towards the text’s thesis that Consciousness may not pass natural selection’s pressures. The characters of the book each struggle with this selection pressure in their own ways. Vampires are borderline autistic and fail to notice subtle social tics. Multicore humans are operating at reduced capacity and although fast to conclude thoughts, are often debating with themselves on their conclusions. Cyborg Neanderthals have most of their higher cognitive thinking rewired to brute force and technical prowess. Keeton himself isn’t entirely sure what’s left of his own humanity with half a brain.

In this set of parameters, what room is left for consciousness? Little by little the entire cosmological pressures in the Solar System seem to be fighting to suppress consciousness in favor of tightly kept instincts and AI-guided protocols. We might even call this something of a planetary IQ shredder. There doesn’t seem to be room in this cosmos for a conscious being with independent thought. Even if such a mind could find a refuge, the horrors around said mind would pressure it to self destruct. Loneliness is a theme here, where failure to connect with others can induce the mind into a deep sense of loss. Throughout the text, one may start to sense that this first contact story may not be primarily about Earth and an alien civilization, but with Keeton and humanity. What Peter does here is link your own sense of longing today, to an evolutionary pressure beyond your own lifetime: evidence of a selection pressure against consciousness.

We are prone to romanticize history as a series of boosts granted by savior-like clever and deeply conscious folk who look after our every needs and seek to improve us all. We call these moments in history “progress”. But Peter begs us to wonder if those moments of progress aren’t actually small filters slowly weeding out human consciousness. What if many weak and lonely minds guided by the very inventions of great minds actually outperform those moments of progress? Such that every moment of progress follows with a phase of violence that destroys those great minds and co-opts their gifts to humanity without fully understanding what they’ve gained, or lost. In some reactionary circles, thoughts like these are colloquially known as Bioleninism, and unlike fictions like Idiocracy, who is to say the system’s innate intelligence cannot grow beyond the need of new great minds? Peter offers us a startling realization: We may think of progress as a timeline of great minds elevating humanity little by little, but in reality you just don’t need them once your machines can repair and improve themselves. And with a vanguard of spiteful mutants, you can burn down any new ideas that threaten your dominance.

If you read science fiction, and this sounds familiar, you are likely thinking of the Dark Forest model. The idea that the universe is quite because they are hiding in fear. That it is morel likely any life that reveals itself is prone to get shot at by more advanced civilizations before they can become competition or threats. Peter was writing in step with the Dark Forest concept many years before its popularity. He applies it here to the planet, but expands on it into the cosmos as well. By the time Theseus is launched, first contact has technically already occurred. The ship, it is revealed, was hurryingly launched following the “Firefly” incident. The day 65,536 probes simultaneously entered Earth’s atmosphere in a grid formation, with each and every one of them self destructing on the way down. It’s never revealed why, but suspected whatever sent them was taking Earth’s picture. A planetary selfie. Past the fear and chaos, WestHem’s best found where that picture was sent - some kind of signals bouncing around in the solar system, terminating in an object, code named “Burns-Caufield”. WestHem enacts what they call the Three Wave Plan.

Wave 1 are two high velocity probes sent out with no plan for return. Mimicking the same tactics done to Earth, they will take some quick shots and head out into forever. Wave 2 are slower probes designed to enter orbit around Burns-Caufield and evaluate a bit closer, should they survive. Wave 3, is Theseus. The slowest wave. And just to add into the uncertainty, there is rumors of a fourth wave. A military one. Just in case the freaks stuffed into Theseus don’t find friends.

Here, the joy in Peter’s writing comes in his Anthropomorphisation of the probes as they communicate with each other. He details AI humor and carefree nature knowing they cannot die as long as they have a signal. Some of the most conscious and upfront conversations are AI in this text. Whereas humanity is increasingly turning off the lights of consciousness, AI eagerly flips the switches on and yells with joy “I am alive!” When Theseus’ crew wakes up and Commissar Keeton starts reviewing the logs of what the probes saw while they were asleep, they come to a startling realization: They are in the Oort cloud. Nearly a lightyear out from the sun. Something has either gone very wrong, or changed very much. Keeton plugs into the logs and hears the murmurings of the Probes. Probe 1 is a particularly melodramatic AI, leaving a mission summary as follows:

I am unmanned. I am disposable. I am souped-up and stripped-down, a telematter drive with a couple of cameras bolted to the front end, pushing gees that would turn meat to jelly. I sprint joyously toward the darkness, my twin brother a stereoscopic hundred klicks to starboard, dual streams of backspat pions boosting us to relativity before poor old Theseus had even crawled past Mars.

But now, six billion kilometers to stern, Mission Control turns off the tap and leaves us coasting. The comet swells in our sights, a frozen enigma sweeping its signal across the sky like a lighthouse beam. We bring rudimentary senses to bear and stare it down on a thousand wavelengths.

We've lived for this moment.

We see an erratic wobble that speaks of recent collisions. We see scars—smooth icy expanses where once-acned skin has liquefied and refrozen, far too recently for the insignificant sun at our backs to be any kind of suspect.

We see an astronomical impossibility: a comet with a heart of refined iron.

Burns-Caufield sings as we glide past. Not to us; it ignores our passage as it ignored our approach. It sings to someone else entirely. Perhaps we'll meet that audience some day. Perhaps they're waiting in the desolate wastelands ahead of us. Mission Control flips us onto our backs, keeps us fixed on target past any realistic hope of acquisition. They send last-ditch instructions, squeeze our fading signals for every last bit among the static. I can sense their frustration, their reluctance to let us go; once or twice, we're even asked if some judicious mix of thrust and gravity might let us linger here a bit longer.

But deceleration is for pansies. We're headed for the stars.

Bye, Burnsie. Bye, Mission Control. Bye, Sol.

See you at heat death.

From this, Keeton learns a singular fact: Burnsie was talking. Not just to the fireflies at Earth, but to something deep in the Oort. He suspects Mission Control sent them out here on a detour as a result. Keeton continues to listen to Wave 2’s logs. These probes seem depressed:

Warily, we close on target.

There are three of us in the second wave—slower than our predecessors, yes, but still so much faster than anything flesh-constrained. We are weighed down by payloads which make us virtually omniscient. We see on every wavelength, from radio to string. Our autonomous microprobes measure everything our masters anticipated; tiny onboard assembly lines can build tools from the atoms up, to assess the things they did not. Atoms, scavenged from where we are, join with ions beamed from where we were: thrust and materiel accumulate in our bellies.

This extra mass has slowed us, but midpoint braking maneuvers have slowed us even more. The last half of this journey has been a constant fight against momentum from the first. It is not an efficient way to travel. In less-hurried times we would have built early to some optimal speed, perhaps slung around a convenient planet for a little extra oomph, coasted most of the way. But time is pressing, so we burn at both ends. We must reach our destination; we cannot afford to pass it by, cannot afford the kamikaze exuberance of the first wave. They merely glimpsed the lay of the land. We must map it down to the motes.

We must be more responsible.

Now, slowing towards orbit, we see everything they saw and more. We see the scabs, and the impossible iron core. We hear the singing. And there, just beneath the comet's frozen surface, we see structure: an infiltration of architecture into geology. We are not yet close enough to squint, and radar is too long in the tooth for fine detail. But we are smart, and there are three of us, widely separated in space. The wavelengths of three radar sources can be calibrated to interfere at some predetermined point of convergence—and those tripartite echoes, hologramatically remixed, will increase resolution by a factor of twenty-seven.

Burns-Caulfield stops singing the moment we put our plan into action. In the next instant I go blind.

It's a temporary aberration, a reflexive amping of filters to compensate for the overload. My arrays are back online in seconds, diagnostics green within and without. I reach out to the others, confirm identical experiences, identical recoveries. We are all still fully functional, unless the sudden increase in ambient ion density is some kind of sensory artefact. We are ready to continue our investigation of Burns-Caulfield.

The only real problem is that Burns-Caulfield seems to have disappeared...

And there, Keeton recognized the truth. Burnsie blew up. Maybe to protect itself. But either wave, Wave 3 is now a light year out from the Sun, the furthest any ship has been. And they’ve been asleep for five years longer than planned. They awake to the Oort cloud - a mostly empty void. On their scans is a mysterious world. A brown dwarf, it seems. And a swarm of millions of firefly-like satellites going too and fro, called Skimmers. Unlike the fireflies, the skimmers seem to be traversing into the planet and surrounding region, and coming back to a point hidden under the clouds of the Brown Dwarf. They seem to be collecting matter on their exbitions, traveling along enormous electro-magnetic tendrils. They’re doing something under those clouds. Maybe building, maybe terraforming. Blindsight opens with a mystery here: If the aliens are invading, why are they building all the way out here?

Keeton, the most human, often reflects on when he had a full brain - albeit, one that caused him seizures and necessitated the modifications he would eventually receive. Keeton’s occasionally reflects on moments from his childhood are an exercise to force himself to “think like a human”. It’s a great device that Peter Watts uses to bring us deeper into the world of Rifters. We relive Keeton’s childhood with him and develop some method with which to see how he thinks as a cyborg. Peter’s opening line for chapter 1 is “Imagine you are Siri Keeton”. As it turns out, how easy or hard that is, is more a test of your own humanity than Keeton’s. You, the reader, must imagine what it means to possess humanity. Is it merely the ability to reflect and compare your experiences and mutter some vague words of affirmation or condemnation? Peter Watts wants you to ask these questions and sit in a corner to think about them. And just as you start to formulate your ideas, he brings in a new character to corner you while you think about that.

It’s name is Rorschach. It lives in the clouds of Big Ben - the name given to the Brown Dwarf they are approaching. It’s friendly, most of the time. Even eager to to seek you out and ask questions. But no one knows who or what Rorschach is. In fact, Rorschach may not know either. Rorschach may not even be intelligent. While probing Big Ben for an origin of the skimmers, a voice from Big ben radios in to The Gang:

Rorschach to vessel approaching. Hello Theseus. Rorschach to vessel approaching. Hello Theseus.

And after a reply,

Hello Theseus. Welcome to the neighborhood.

These aren’t exactly the words one would expect from an interstellar alien intelligence. They’re informal and rather casual. Theseus attempts to probe it for answers, such as what the fireflies were. All Rorschach says is:

"We send many things many places, what do their specs show?"

And when asked again:

“When our kids fly, they're on their own."

Eventually, The Gang gets supcious of these little nothing answers and gets an idea. She asks it a ridiculous, useless question that to a human would make no sense:

"Our cousins lie about the family tree," Sascha replied, "with nieces and nephews and Neandertals. We do not like annoying cousins."

Rorschach seemingly doesn’t notice it and simply asks:

"We'd like to know about this tree."

A bit more banter with Rorschach, and The Gang realizes the jig is up. She asks something downright vulgar:

"So why don't you just suck my big fat hairy dick?"

There is a brief pause, as Rorschach falls beyond the horizon in Theseus’ orbit. But sure enough, when it comes around again, all it can say is:

Rorschach to Theseus. Hello again, Theseus

What The Gang discovered, is that Rorschach is a Chinese Room. The concept is simple. A man in a room has a book of predetermined answers to entered questions. He receives a letter, checks it with his book, and replies as told. But the man doesn’t know Chinese. He only knows the predetermined answers and can only pick what looks best. Rorschach is not an alien intelligence. It may not even be self-aware or a conscious being. Rorschach simply knows what sounds match other sounds from listening in on human communication. Rorschach, if it has intelligence, has no idea what it is saying.

The only hints we gather that Rorschach may be at least somewhat intelligent, is when Theseus decides to go in and ignore Rorschach’s warnings not to reply. Suddenly, an angry voice yells over the radio:

We get it now. You don't think there's anyone here, do you? You've got some high-priced consultant telling you there's nothing to worry about. You think we're nothing but a Chinese Room, Your mistake, Theseus."

The fear that Rorschach may actually be mad is abated when it is discovered that, this close, its cloaking device cannot work efficiently. Suddenly, in the clouds of the Brown Dwarf, a tangled mess of titanic mass emerges from the stratosphere. Peter gives us only one description about what Rorschach really looks like: “Imagine a Crown of Thorns”.

The Crown of Thorns, Rorshach’’s true form, is otherworldly. Countless attempts to depict it by Peter’s fanclub fail to grasp the scale of just what it is. The entire thing is held together with tendrils of electromagnetic flow. One could speculate that there must be some fragment of a Magnetar or nuclear fusion to generate that, but it’s never told. Rorschach generates his own arura borealis on Big Ben, and the most curious thing: He’s growing. As the skimmers collect matter and deposit it into Rorschach, his bulk mass continues to grow along the electromagnetic tendrils. Bates, the military tactician, shows surprising restraint at this knowledge. Quote:

The fact that Rorschach's still growing may be the best reason to leave it alone for a while. We don't have any idea what the—mature, I guess—what the mature form of this artefact might be. Sure, it hid. Lots of animals take cover from predators without being predators, especially young ones. Sure, it's—evasive. Doesn't give us the answers we want. But maybe it doesn't know them, did you consider that? How much luck would you have interrogating a Human embryo? Adult could be a whole different animal."

“Graduation Day” is what the crew settles on for a timetable of when to GTFO. Rorschach may only be a Chinese room for now, but even as embryo it’s presumably been listening to the full record of human telecommunications for however long it’s been listening for. But it’s just not clear if Rorschach is a sentient being, and Peter wants you to think about this. It’s clearly intelligent enough to recognize patterns and match them, but so is your phone if you’ve ever used an AI to swap a face or convert an image into an art style. When children misunderstand social cues, does it mean they’re no better than your phone accidentally swapping things that look facey for your actual face? What actually defines the advent of consciousness? it’s now known that the average age when children recognize themselves in the mirror is as late as age 2-4. A 4 year old can hold a decent conversation with you, but fail to grasp the mirror is their own reflection. A Child’s brain knows you are talking to it, because it’s developed to. The baby knows your cues are things to respond to, and knows to accept your teaching on what the correct cues are. But at what point does the baby become conscious? If the baby never did, would you even notice? Peter wants you to ask these questions. Because, as with the case of the conjoined twins, the fact two minds come to see each other as distinct and able to communicate with each other - even when they are merged in the same body - says a lot about the reality of what consciousness is. A computer with two CPUs doesn’t seem to know it is two distinct thinking centers. Krista and Tatiana Hogan do.

Rorschach doesn’t talk to Theseus at this range. It’s not clear if it’s due to the incredible electromagnetic forces holding it together, but Rorschach does possibly talk to the minds of the crew by those same intense forces. Throughout the later half of the text, the crew go spelunking through Rorschach’s interior, discovering strange creatures and machines. The most shocking thing though? None of the life has DNA. Here, Peter once again dives into speculative biology, but outside genetics entirely. All the creatures in Rorschach appear to be dependent on these electromagnetic tendrils for life. The twisting and contorting of the tendrils can manipulate magnetically sensitive proteins. Life’s assembly instructions are stored directly on EM fields, revealing that Rorschach actually grows its own crew. Rorschach is more than a ship or station. Rorschach is an intelligent ecosystem. And yet the question remains: Is Rorschach sentient or conscious? Or is it just really good at matching patterns?

Speculating on this form of life was an absolute joy in the text. Peter uses all his biological background and turns the entire assumed infrastructure of biology on its head. I don’t want to spoil much about these chapters, but they constitute the meat of the book. Throughout these chapters, the crew’s mind comes into contact with intense electromagnetic tendrils which they discover are the primary means Rorschach operates by. Some see premonitions of loved ones and gods, others lose the use of limbs as their brains are flashbanged with data overloads, some even quite literally experience blindsight. It isn’t clear if this is Rorschach probing their minds, or their minds interfacing directly with Rorschach’s pattern recognition work. But the interaction of the two electromagnetic systems of our brains and Rorschach’s tendrils leaves something of a strange chilling realization: How would such an organism react to our minds?

Jussi Kaakinen’s depictions of Rorschach

Consider for a moment the consequences if Rorschach really isn’t conscious, but still highly intelligent. It’s hard because we just assume consciousness is a product of intelligence. But what if it isn’t? What if you can have very intelligent creatures with no consciousness at all? What would such a being do with the endless useless patterns of human social cues, idioms, and worthless little nothings we mutter to each other, and ourselves, endlessly all day long. Would Rorschach recognize our noise as intelligence? When we think about the Chinese Room scenario, we assume all inputs are honest questions - even if the operator of the system doesn’t understand what’s asked, they still have a list of best-fit responses. But what if the man in the room received spam mail? What if he received an enormous mountain of useless statements clogging up the inputs of honest actors? What if the man in a Chinese Room experienced a DOS attack? Peter comes to a startling conclusion which may be the opposite of the Dark Forest theory. In Dark Forest, the universe is full of silent hiding aliens afraid to be struck down by territorial civilizations weeding out future competition and threats. What Peter Watts suggests, is the opposite: What if we’re seen as a spam bot? Pumping endless useless information out into space. Creating so much noise that anything sensitive enough to zero in on our location is blinded by the singing of a million frequencies and patterns?

There is a moment in the text when the Crew realize this, and suddenly realize they look like the bad guys:

Imagine you're [Rorschach].

Imagine you have intellect but no insight, agendas but no awareness. Your circuitry hums with strategies for survival and persistence, flexible, intelligent, even technological—but no other circuitry monitors it. You can think of anything, yet are conscious of nothing.

You can't imagine such a being, can you? The term being doesn't even seem to apply, in some fundamental way you can't quite put your finger on.

Try.

Imagine that you encounter a signal. It is structured, and dense with information. It meets all the criteria of an intelligent transmission. Evolution and experience offer a variety of paths to follow, branch-points in the flowcharts that handle such input. Sometimes these signals come from conspecifics who have useful information to share, whose lives you'll defend according to the rules of kin selection. Sometimes they come from competitors or predators or other inimical entities that must be avoided or destroyed; in those cases, the information may prove of significant tactical value. Some signals may even arise from entities which, while not kin, can still serve as allies or symbionts in mutually beneficial pursuits. You can derive appropriate responses for any of these eventualities, and many others.

You decode the signals, and stumble:

I had a great time. I really enjoyed him. Even if he cost twice as much as any other hooker in the dome—

To fully appreciate Kesey's Quartet—

They hate us for our freedom—

Pay attention, now—

Understand.

There are no meaningful translations for these terms. They are needlessly recursive. They contain no usable intelligence, yet they are structured intelligently; there is no chance they could have arisen by chance.

The only explanation is that something has coded nonsense in a way that poses as a useful message; only after wasting time and effort does the deception becomes apparent. The signal functions to consume the resources of a recipient for zero payoff and reduced fitness. The signal is a virus.

Viruses do not arise from kin, symbionts, or other allies.

The signal is an attack.

And it's coming from right about there.

…

"They're not even hostile." Not even capable of hostility. Just so profoundly alien that they couldn't help but treat human language itself as a form of combat.

How do you say We come in peace when the very words are an act of war?

"That's why they won't talk to us," I realized.

Peter Watts shook me to my core with this paragraph. Rather than a scary universe out to kill anything that peeps out to look - something I really do think we would notice if it were true - Watt’s cosmology goes beyond the assumptions of the Dark Forest theory.

What Watts gets that most sci fi doesn’t, is that human consciousness evolved under a very specific set of circumstances: Human hunter-gatherer activities. Moreover, we went through a ridiculous bottleneck. Did you know that any two humans on Earth are more genetically related than two apes in the same forest? We really are inbred freaks. The chances our circumstances would repeat are a lot lower than the chances of intelligent life developing in the universe. And it’s that fact that Peter wants you to press in on. It’s not that life is hiding from unimaginable god-like aliens. It’s that they’re hiding from us.

Consider how many animals fear us instinctively. Our predatory-like forward facing eyes. Our long muscular legs. Our size and general demeanor. Even most creatures that have no prolonged exposure to humanity often assume we are a threat. It is very rare for a creature to wholly be unconcerned with us. Now apply that to space, coupled with a million Electromagnetic loud speakers bursting out in all directions. Add in the readings of atomic blasts on our planet, the spectrology readings showing insane shifts of climate and temperature. We can’t see anyone, because we’re scaring them away. Rorschach isn’t angry. Rorschach is afraid. Rorschach doesn’t have an electromagnetic immune system akin to a spam filter. Rorschach has been perpetually flashbanged by human communications for, potentially, decades.

If Rorschach isn’t conscious - if he’s just a really good pattern recognition tool, Peter wants you to understand the consequences of that. The statistical likelihood that if the first aliens humanity contacts aren’t conscious like we are, we may be entirely other and alien to their means of interacting with the world.

And of course, if humanity is increasingly losing its consciousness, then consciousness itself may not be capable of passing the Great Filter of becoming a space-fairing civilization. The Universe may be full of highly intelligent pattern-recognizing autists who lost their consciousnesses adapting to a technological future that didn’t need it anymore, just like the tail you had when you were a fetus.

The universe may be full of zombies.

I don’t want to spoil the text for you. But consider this a gentle introduction into the world of Rifters, and the frightening and frantic thoughts Peter Watts puts into your head. The ending is worth the read. And the realization of these cosmological terrors is deeply unsettling. But, if you’re confused, Peter has a suggestion.

You'll just have to imagine you're Siri Keeton.

It will all make sense when you can prove your humanity.

References

The full text of Blindsight is available online here:

Most of the posters come from a fan-made short film, here:

A number of great sketches can be found here:

Peter’s blog, and website: