Breaking a Frame

And framing a break

Dear Reader, this one’s too long for email, so give a read at the Substack!

Art exists to be framed, does it not? It must be controlled in order to be enjoy-(ed/able). If paint, in a literal frame; If performative, the stage; If experiential, some room secured with lock and key. We don’t often consider the bondage we place on art, but it’s quite obvious why if you think about it for even a moment. After all, we have a word for art that escapes its cage: Politics.

And politics can be scary.

When art does escape a frame, it is difficult to imagine it as politically neutral. Graffiti, for instance, will often displaying unspeakable criticisms - or even its mere presence will spark anger and debate. In my local neighborhood, there was a pile of ruins used for graffiti, called 5Pointz. The owner decided to white-wash the building and tear it down. This was seen as rather inciteful. Why paint the building white if you plan on tearing it down anyway? But, of course, he was the owner and had the right to do as he pleased. There followed a lawsuit by the artists, and they actually won. Such is the strange happenings when art escapes its frame.

In the long history of artistic pursuits, the caging nature of the frame has usually been treated more-so as guide than oppressor. I recall in university during a art course one assignment where we would paint a picture with all our colors and tools, and then paint it again using only charcoal. To many a surprised eyes, the charcoal painting was nearly always superior. The reason being, constraints force innovations. Contrarily, freedom produces a regularity with normative gestures.

But occasionally, artists have arisen who viewed the frame as a constraint to escape, and wished to see their art uncaged - to witness what their art could do roaming free in the world. In every instance, I would argue, the transformation into politics was an inevitability rather than a risk.

One of the more famous examples might be Gordon Matta-Clark, who in the 1960s and 70s would routinely cut monolithic holes into abandoned buildings as something of a material graffiti rather than an aerosol kind. He was the only artist who would ask if he could remove the museum’s wall rather than add to it.

Of course, being an artist in 1970’s New York, it’s hard to tell if many people even noticed the random holes cut into buildings. If anything, in some instances he improved the ruined parts of the city.

Perhaps in an ironic twist, his having died of a pancreatic cancer cutting holes into his body was his final contribution to the realm of deframed art.

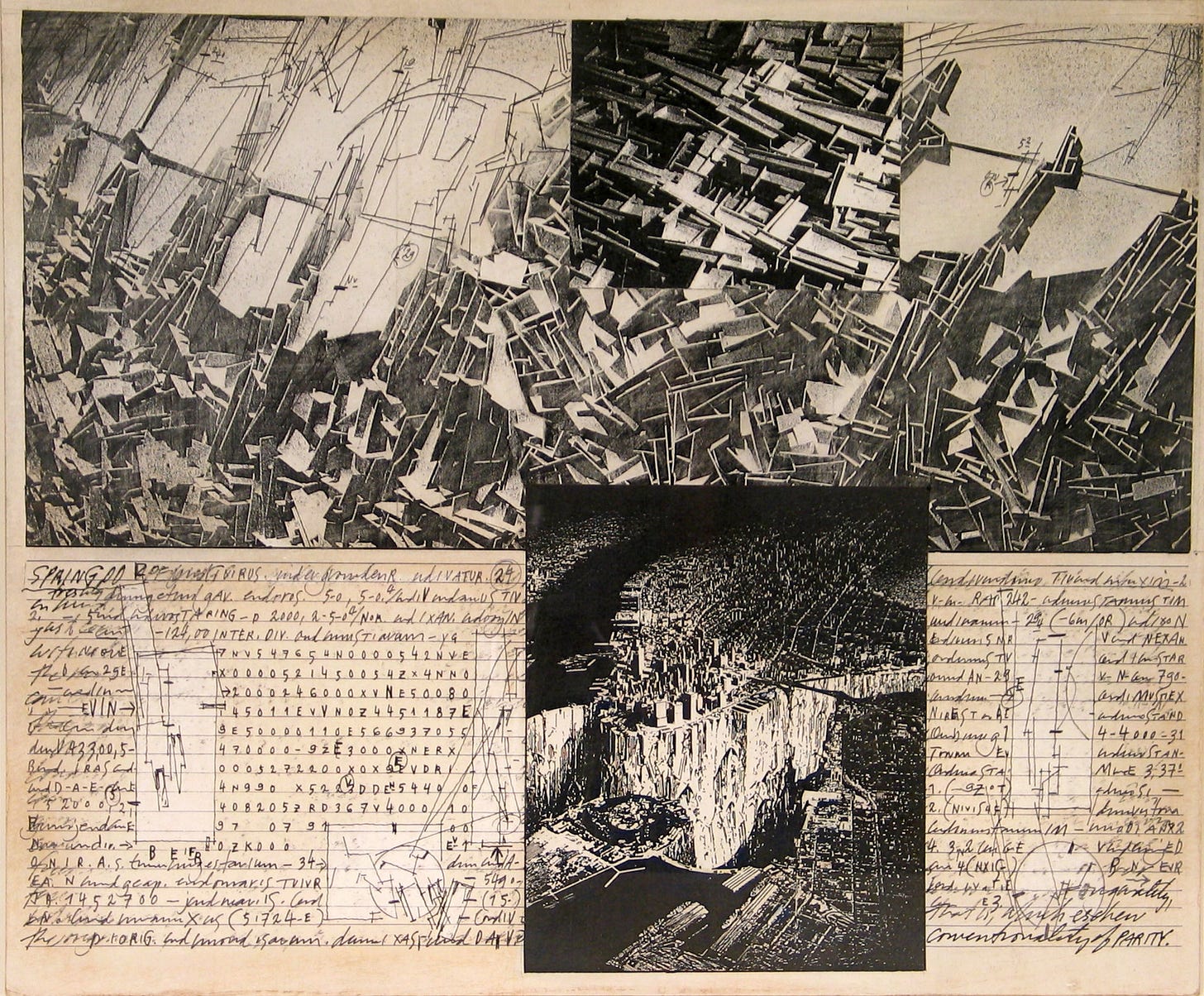

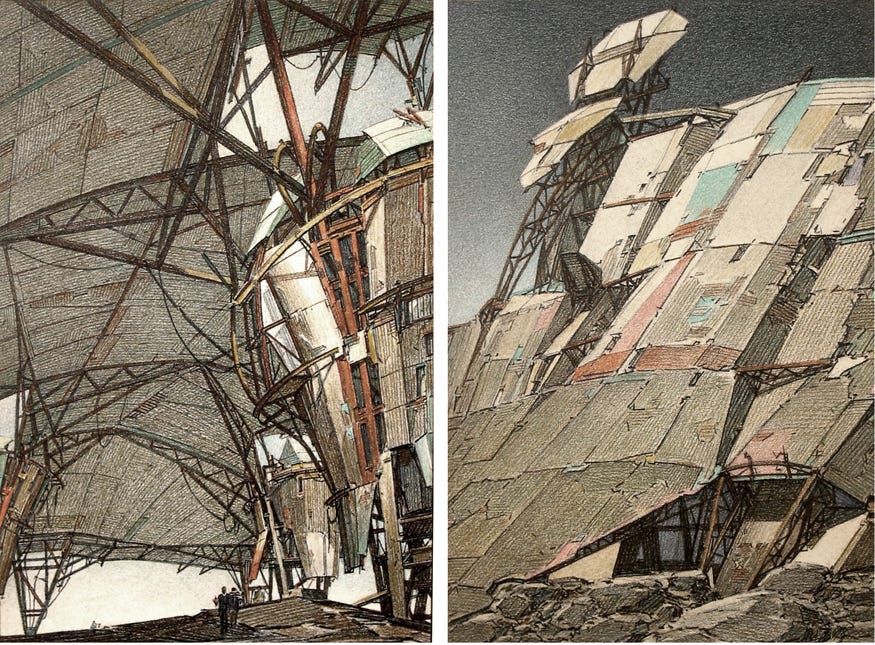

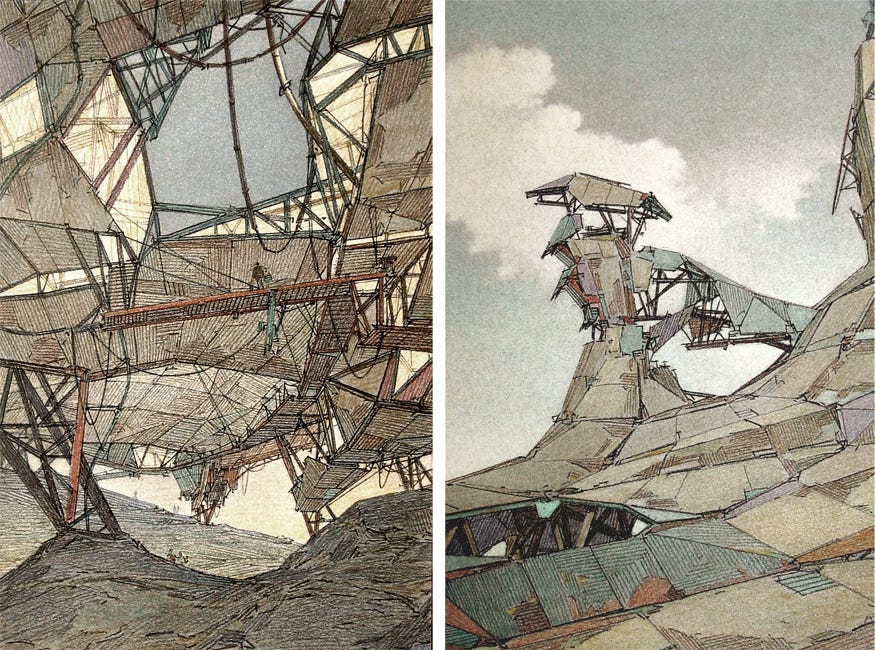

Another mind to be your guide in contemplating this re-framing of art would be Lebbeus Woods - and early influence in my own field of work in architecture. He is known primarily for what some consider a carnivorous form of architecture:

It is often difficult to put to words just what exactly Mr Woods is designing here. He rarely explains his drawings. They simply grab your attention as you can work out familiar things being consumed by unfamiliar, strange, tectonic carnivore. He is sometimes compared to the more biological H.R. Giger, but Mr. Wood’s designs are distinctly sharp in form compared to Mr. Giger’s orgasmic curves. Whatever it may be, Mr. Woods displays an architectonic system that has escaped the frame of building lots and height regulations to break into the world and consume.

In many ways, Mr Woods is a curious litmus test for architects. You either “get it” or you don’t. Very few know about him outside of the field, and those that do, tend to over-indulge without proper architectural training. I’ve noticed some rather obvious similarities in games such as Half Life, for instance. An Architect wouldn’t copy so blatantly methinks.

It should thus be unsurprising that Mr Woods dabbled in matters political, developing something of a manifesto centered around the concept of Heterarchy. Mr Woods viewed heterarchy and hierarchy as in something of a ying-yang relationship, with ordinary anarchy outside the scope of either. He defined Heterarchy as follows:

In the past, it was the principal task of architecture to monumentalize the most important institutions of culture by the creation of an urban hierarchy of forms and spaces that correspond in a physical way to the hierarchy of authority embodied in the institutions themselves. Today, even though hierarchies of authority necessarily remain in place, a new system of order has taken root in global urban culture: the heterarchy.

The heterarchy, or network, is a system of organizing space, time and society comprised of autonomous, self-inventing and self-sustaining individuals and groups, the structure of which changes continually according to changing needs and conditions. The individual living within such a system is characterized by the existential burdens of freedom, but also by the singular rewards of bearing them without illusion.

The manifestation of heterarchies in the contemporary city is largely hidden, because it emerges from within spaces of individual living and works invisibly from there outward. It exists as elusive, ephemeral, continually changing pattern of free communication emanating from and received within isolated, yet distinct spaces of habitation.

One may relate this to such political concepts such as Moldbug’s Cathedral. Don’t be surprised, however, that architects developed such a theory decades before politics did. I have four thousand years of historical examples of this happening. It’s nothing new.

What Mr Woods sought, was an architecture to enabled these political forces to leave their frame and occupy any space - what he called “Freespaces”. This led to a very curious entry to the 1988 Korean DMZ competition, in which Mr Wood’s Heterarchy uplifted above the mined and shelled wasteland to create a meeting place among enemies. Floating neutral territory:

Thus Lebbius Wood’s de-framed architecture could provide the spaces in territorial gaps to formulate new solutions.

Ok, ok. There’s probably some autist out there who will fight me on this dichotomy of the art framed or unframed, and I am sure there’s a lot of specificity along the ins and outs of this differentiation. Suspend all that for a moment. Or, leave a comment on examples of art-on-the-loose that isn’t political. I’d love to read about it. Besides, the point to be received is not about art-on-the-loose, but rather the inverse: A great way to contain politics you don’t like is to weaponize art. To frame it in a cage. To contain it.

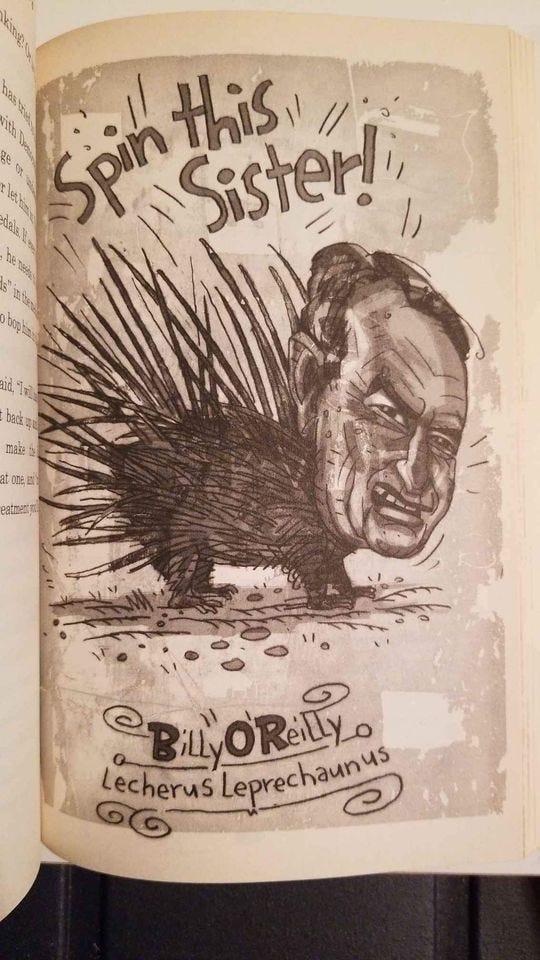

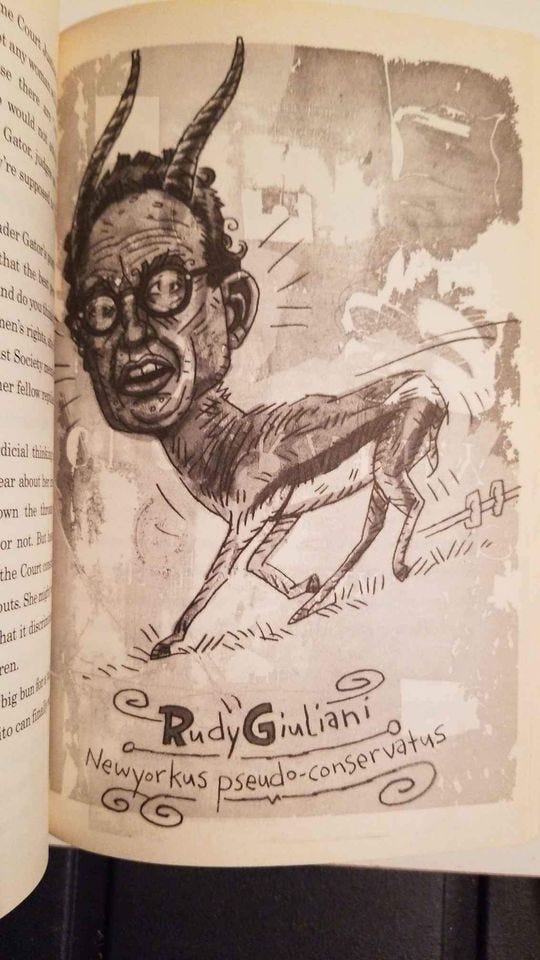

To explain this weaponization of Art, let’s take a retreat to the fond early 2000s, that wonderland where the afterglow of 90’s joy still emanated. Most of you probably have memories of either your dad, cousins, uncles, or really any older men you knew listening to talk radio. I certainly do. Most of my weekends as a kid in those days I would spend with my dad renovating the apartment complex my Grandmother purchased in the 1930s, and all the live-long day I would hear the march of conservation arguing about many a topic. My favorite was the bitter old vocals of one Michael Savage - mind you, not because I agreed with much he had to say, but because he often was the problematic one. He was obviously insane, but they kept him framed in his little corner of the airwaves. And his obvious frustration with being caged amused me. Mr Savage also wrote, and I have fond memories of The Political Zoo: his art book.

The text was Mr Savage’s best attempt to explain the regime we live under in the grey years of the 00’s, and while he projects himself as the zookeeper, tending these beasts is really the job of the regime at large. Zoo is an apt term I occasionally hear brought up by dissident (w)ri(gh)ters today, so if you’re curious as to the origin of that term, this is for you.

Mr Savage’s Zoo is an artform of equality. He goes after both wings of the Turkey. He has plenty to day towards Democrats, but also many an amusing note towards Republicans as well. Every animal in this zoo has a nature to it, with which the zookeepers must acquire specialized knowledge to deal with in order to maintain the health of the beast. But this specialized knowledge also has an important primary task as well: train the beast to perform on-demand as needed to entertain the zoo’s visitors, that being ourselves.

I don’t know if Mr Savage ever caught on to what he was doing, but in framing politics as performance animals, he was actually identifying the means by which the Regime uses art to keep the zoo under control - to keep it as art, and not as actual politics. The pages of Mr Savage’s books are full of pundits past and present. Some of the youth today may remember these beasts, others have already been forgotten in favor of new performances. Yet still some ring rather prophetic for a time not yet come.

Hidden away in Mr Savage’s Zoo, near the end, one finds perhaps the most prophetic page of them all: Donald Trump. Back in 2007, Mr Trump was still an avowed Democrat and liberal. For Mr Trump, he writes thus:

It has been some 15 years since Mr Savage penned these words, and the Balding Eagle’s else-ware roosting has moved from mate to domesticity.

The animals must stay in their cage, because if they get out then everyone at the zoo won’t be very happy.

His criticisms of Soros are especially curious. One can find here something of a reflection of himself. Savage himself, of course, was a performer too. A Secular Jew with some nefarious homosexual histories, much denied. In his hey-day, Savage talked often about faith and reason - fields of expertise for him not because they were forces molding him, but because he was a performative actor who had mastered the display of them. There is here a certain revelation that the Zookeper, too, is a kind of extra animal in this Zoo. He too performs tasks on-demand, and he too must keep the guests entertained. His zookeeping skills contribute as much as the animal’s acts, and he too must master what he has been trained for.

Savage was, and remains, an atheist in all practical terms. But like Carl Benjamin and Richard Dawkins today, a secularist can at least understand the value of art they feel they can control, so long it remains controlled, of course…

(A few more slides for your enjoyment)

De-framing and Re-framing seems to me to be the border between art and politics. Any politics which becomes captured becomes an art to be enjoyed in a secured environment. Any art released from its frame breaks out into a political force on creation. This is why you can meme political extremism into containment, and you can release a contained politik by releasing an artform from its frame.

Once upon a time a comedian told me an historic anecdote about Pablo Picaso. It is said he would hold an unloaded revolver where he worked, and if anyone unfamiliar with him dared wonder by and critique his bizarre forms, he would take out the pistol and fire it at the critique. Shock of the passerby would turn to calm as he realized he was still alive, and Pablo would wink and go back to work. The comedian told me “Thank God no one ever booted him from art school.” But I would argue, Pablo simply did not desire his art to leave his frame - that was someone else’s job.