Korean history is a curious microcosm. For one reason or another, the medieval history of the peninsula is more similar to a Modern European state than a Classical Asiatic despot. By the eighth century, Korea has a constitution-bound monarch, an empowered parliament, and a sophisticated knightly order for the peasantry to move up in social hierarchy. By the 16th century, it has some of the highest literacy rates and technological advancements in the world. Then, suddenly, it all got stuck. It became rigid, stale, and seemingly lacked a will to live. Within two hundred years it was split open like a dying boar and devoured by colonial powers, and it’s never really recovered since.

Due to its isolated nature, it’s much easier to identify the factors that contributed to its rise, stagnation, and fall. Western readers can find a number of parallels to their own national stagnations post-empire thereupon.

Starting around the Seventh through Ninth Century, Medieval Korea faced a competency crises that began to cripple all aspects of their state. The embedded aristocracy had grown decrepit and hated by the people. But, perhaps most shocking to the modern reader, is the fact the government acknowledged the competency crises and sought ways to resolve the problem. This would prove a turning point in Korean society, as the desire for the existing aristocracy to hold onto power butted up against a growing self-awareness that they lacked the capacity to fix their own problem.

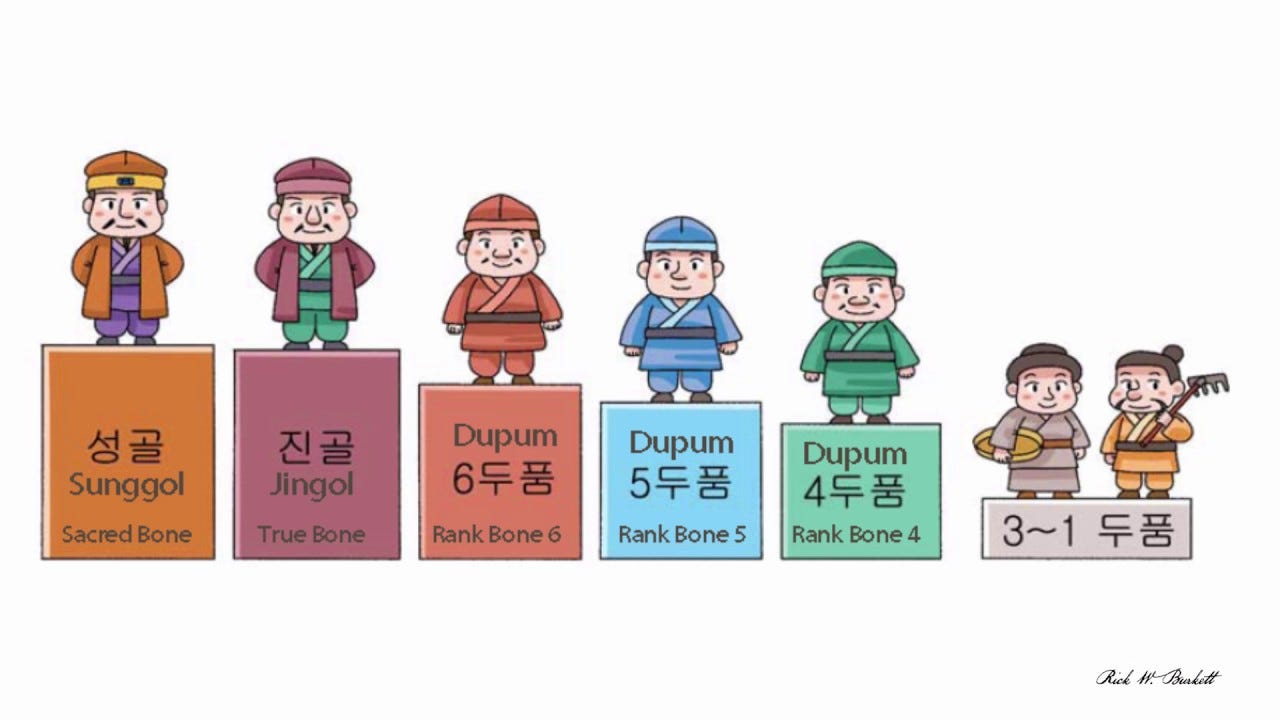

Korea, at the time, was organized around a rather ancient “Bone Rank” system which likely had origins going back to the stone age. Aristocrats were ranked according to the purity of their bone, which seems to be a parallel to the blood purity rankings of medieval European dynasties.

This bone ranking system took into effect caste-mixing, with ranks for mixed and pure bones that influenced how high a position someone could achieve. The Competency Crises primarily arose from Koreans not feeling motivated to work harder once they reached the highest level their Bone Rank allowed.

Due to these limits, many Koreans of mixed Bone heritage began moving to China to take their chances with the state exam system, which would open new opportunities for them. The Chinese system allowed them to get jobs off of competency, rather than heritage. One such 10th century monk, Choe Chiwon, managed to earn a rather high rank, and work at the prefecture level of administration (answerable to the Emperor directly). His efforts are recorded in a poem he wrote about his experiences, working in higher ranks than he could ever achieve at home in Korea:

Who is there within China to sympathize with him without?

I ask for the ferry that will take me across the river,

Originally I sought only food and salary, not the benefits of office,

Only my parents’ glory, not my own needs.

The traveler's road, rain falling upon the river;

My former home, dreaming of return, springtime beneath the sun.

Crossing the river I meet with fortune the broad waves.

I wash ten years of dust from my humble cap strings.

He was only 28 when he retired from his Prefecture duties to return home, but he returned to a Korea in a state of near-collapse. The royal government had declined to a minstrel show in the capital, and the peninsula was now ruled by warlords exercising private armies. The most famous of them, Jang Bogo, was running what was effectively a pirate state along the coast. He submitted a 10-point reform guideline to fix the competency crisis, but royal sponsorship meant little in the time of war lords. The aristocracy wouldn’t budge. He scoped out the warlords and picked one that looked promising. Wang Geon, who incidentally would go on to reunite the peninsula under a new dynasty. Another of his poems survives to express his mixed disappointment and hope at the state of the decline:

The leaves of the Cock Forest are yellow, the pines of Snow Goose Pass are green.

Silla, the ruling dynasty, was named after the Rooster. Snow Goose Pass was Geon’s homeland. The implication was, he was tossing his hat in with the war lord.

Wan Geon would implement Choe’s 10 point reforms and institute a state exam, like in China, to award positions off competency rather than hereditary relations. Called the Gwageo, it not only measured one’s knowledge, but also ability to use it.

Soon after, Medieval Korea had an ascended peasantry stirring new and innovative industry, allowing Korea to stand on its own against regional players in Japan and China. Although Medieval Korea had an existing constitutional monarchy answerable to a parliament of noble families, this had become stagnant and the direct monarchy of Geon proved more capable of opening up the Bone Rank system. However, Korean history began to enter a stagnant phase yet again starting in the 1500s, which continued through to the 1800s, culminating in the Japanese occupation and colonization in the 19th century.

Despite a return of its independence after the war, Korea has remained rather colonized, now by the global economy instead of Japan. Even their recent ascent in the realms of entertainment media, technology, and cosmetics remains in the shadow of a broader globalist power structure. Birth rates remain low, architecture remains glass and steel, entertainment remains within the Hollywood structure, and there is a sense of being “stuck”. Stuck culture, as some have put it.

In C. Fred Alford’s “Think no Evil”, an evaluation of Korean Values in the Globalist Age, he points out the problem in the lens of Korean Poetry, once a deeply intimate and unique experience, which has essentially been stuck for a few decades:

This problem can be broadly extrapolated across all participants in the global economy. We’re stuck. We can’t break out. We seem to lack even the will to break out. We seem too comfortable.

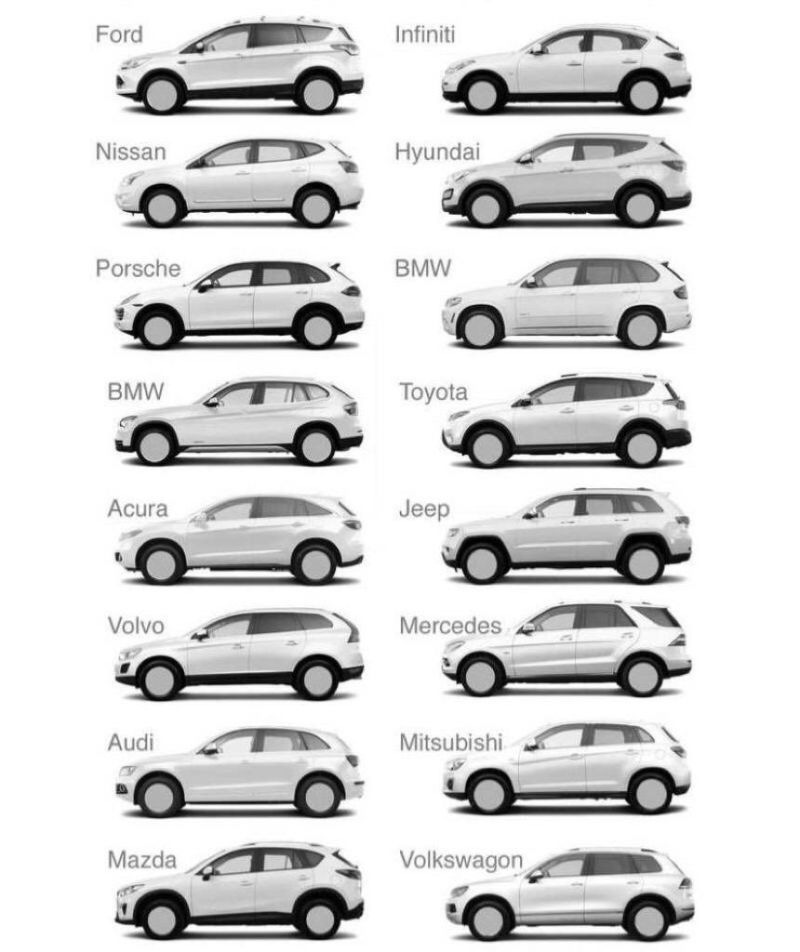

In his article “Culture is Stuck”, Tom Littler shows this in a very direct way, posting a photo of all new car models pointing out nothing is unique. It’s all conforming to the same optimized norm.

Of course, we do have to accept that there are ideal forms which express a maximumly efficient product. And this, perhaps, hints at the problem. Rather than looking at how to express our souls, we are looking to how to most efficiently “be”. But optimizing one’s experiences and behaviors does not a culture make. In fact, sometimes culture is born out of a distinct avoidance of efficiency.

As an example, to treat Korea once again as a microcosm case study, one can remark this avoidance for pure efficiency in their Bronze and Iron Age. Reason would imagine Korea would primarily rely on China for their trade, but Korean trade had a remarkable avoidance for the most efficient trade route in favor for the most direct to distant partners. There was, to be clear, strong trade with China and Japan. However, the Korean medieval state seemed to seek primary access around China to avoid local influence at times. This appears to have stemmed from a desire to innovate on their own, apart from Chinese influence. As a result, you will find a surprising amount of Scythian and Indian influence, from bypassing Chinese routes. Koreans opted to run their trade routes through Siberia to Scythian sources, and cross sea routes to India, in order to most directly come into influence from other sources. As a result, Medieval Korean cultural artifacts are a strange hoshposh of Indian and Scythian details overlaying an Asiatic template. Their crowns feature the World Tree motif found among Indo-European mythology, and their armors looks more similar to Persia or Byzantium, than that of China.

We Americans have suffered something of a similar stuckness. When we were a young nation, we drew from European, Indigenous, and Ancient sources alike, fabricating something distinct from any of the source material. However, since our ascent to global dominance, where are these faculties? Do the particulars of Ancient Rome’s governance, or the particulars of Indigenous council-fires, or the particulars of English Common Law come to the forefront in our global presence? Not much. Nearly the entirety of America’s global exports today stem from ideals no more than 60 years old, with the original creative energies limited and quarantined to small niche interests.

And so, we remain stuck. The culture, technology, and general experience of our civilization remains stuck in some Civil Rights idealism that fails to actually be civil or protect rights. What is to be done?

History has shown that the only way out, other than getting colonized, is a kind of war lord figure who has a goal of returning to a civil society. This is rare, and not something that can be trusted. Most war lord figures ultimately end up serving their own power. But there’s also another factor. America is not a military-based society like those of the past in these situations. It is an economic power. What would an economic Caesar figure look like? Rich, to be sure. But he’d have to be honorable. This is even rarer than the honorable War Lord.

So we remain stuck, doomed to be colonized in our stagnation, until this figure emerges - if he ever does.

Howe would you attempt to bring forth such a figure?

How? I feel the growing need in this time is a burning down. Make room for the movers and shakers from outside the Orthodoxy. As with that monk, as with those men of motion in South America, Meso America, the Pacific Islands, they only got to fix things when the alternative was untenable.

For all the faults of Korea, Japan, America and Europe our cultures are yet still comfortable enough to stay the torch.

For now. Maybe this election will see a Sulla figure make the bandaid fix an emperor type will rip off.

Thanks for a bit more insight into Korean history. It's weird how extensive, poetic, and well documented it is and yet hardly spoken about. It's much like Eastern mythology as a whole, where the West simply doesn't get great compendiums of the stories like we have about our own pantheons and fairy tales. I don't want to hear about son wukong again, I want to hear about who the hell Cheok Jungyeong was. I want the explanation as to why it is the Hermit Kingdom. I want to understand the aesthetic difference between a Korean 'knight' and a samurai.

Fascinating, as always. Oh, and glad to see the Restoration Bureau is stirring, too.