I was recently invited to give a short speech on networking through decline. This is something of a transcript. It borrows from a previous substack article, linked at the end.

Imagine you are French.

My apologies if that triggers some instinctive sense of disgust. Nonetheless, imagine you are a citizen of the city of Orléans. Imagine you are a citizen in that old European city. You’re surrounded by cobblestone roads, plastered buildings, and the subtle breezes that pass the hills and valleys of your beloved Countryside.

As far back as you can recall, you knew the land by the tongue you spoke. In fact, you likely have some pride in your rather unique way of speaking. You can easily hear a fake, because it is so very difficult to learn the accent without growing up in it. You speak your way, everyone else shouldn’t. You had leaders that spoke like you growing up. They looked like you, and prayed like you. You understood your polis, and your polis understood you.

However, things have been feeling a bit off recently. Your officials have started allowing a large number of refugees into the city. They aren’t like you. They have been quite riotous! After a few years of this messy and deteriorating situation, it was decided by your government to install a new governor for the region to bring some order. But, much to your surprise, this new governor is not like you. He is like them - he barely speaks your language, and doesn’t really care about your values or religion. He’s simply here on orders to bring order. But oddly, he only seems to bring order to his own. This is confusing for you. Cathedrals have been burned, shops ransacked, and you can’t help but feel you’ve been made a foreigner in your own city which now has a foreign leader.

In fact, you might be noticing people that look like you are, increasingly, rather rare. Perhaps you ought to acquiring a weapon for self defense? Of course, your government forbids this. Yet they seem perfectly ok with the armed imported administration they tolerated all around you. Indeed, as you tread across the decrepit and unmaintained cobblestone walkways of your city, you can’t help but wonder if your leaders may even be actively trying to do this to you. How did your beloved Orléans come to this? Why have they allowed your streets to rot and crack while barbarians break and bash?

Your mind is getting cluttered by these thoughts, when suddenly a noblemen approaches you with a group of loyal men. He sees your expressions and knows your mind is like his. He offers you a weapon and a promise to protect you if you serve him.

Do you accept?

I must confess something. You likely imagined my description pertains to contemporary conditions. However, this description is not of 2023. It is the Orléans of the 5th century.

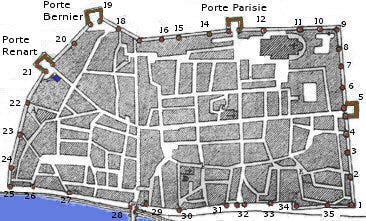

Aurelianorum, the Roman city that became Orléans

I want to talk to you about building new things while everything is in decline. And as I’ve been told you’ve all thought about the Roman Empire at least once today, I want to use this Roman Ghost Story from Gaul as a framework

Roman Gaul had seen devastation in the Crises of the third century. It had likewise made an impressive recovery through the fourth. Peasants were returning to the farm, and the nobles were building generational wealth. Rome’s first factories were invented by this same competent class. In fact, the traditional Roman legionnaire armor had been invented in Gaul, centuries prior. These people were competent ,and in these days Rome didn’t want to prevent that from stirring innovation. The Imperial government had mostly ignored the blatant tax evasion of the region because it produced good soldiers, grain, and a competent class of officials they could use to tax everyone else in the Empire.

Things weren’t great, but they were stable. On closer inspection the initial wealth of the past century had started to peak the interest of the Empire. They had started taking soldiers off the Rhine to go fight elsewhere. The taxes had gradually gone up to compensate for the legendary tax evasion of the Gauls. Into the 5th century, the Romans had started to tap into that wealth. Tolerable at first, now increasingly a bit too much.

But the situations in Gaul changed in the final days of the year 406 AD. In the years prior, dark forces from the East had begun raiding Germany, and the refugees of those wars had started to form camps along the Rhine, begging Rome to let them into the Empire. They promised to be good workers, worthy friends, if they but had somewhere to call home. But Rome had experience with Germans.

The answer was no.

But, that year was different. In 406 AD, the Rhine froze over, and suddenly those Germans who had been asking to come in, started coming in without asking. They had considered if taking the newfound wealth of Gaul was worth the risk of a legion, but with this highway straight into the heart of Rome’s rural countryside, they knew they could take without asking.

Crossing of the Rhine, 406 AD

They started trickling in by the dozens, then the hundreds, then the thousands, then the tens of thousands. Tribe after tribe crossed the frozen Rhine seeking Gaul’s generational wealth. Quadi, Vandals, Sarmatians, Alans from Iran, Gepids, Herules, Saxons, Burgundians, Alemanni Goths, and more. All the way from Pannonian in the Balkans. They crossed the Rhine, fleeing eastern invasions and seeking Gaulic Wealth. The general in charge at the time, Stilchio, was half Lombard. And many historians think he couldn’t bear to attack his own. So he stood down, and let them cross.

The migration period had begun.

New Years day dawned January 1st 407 AD, and the Roman Empire now had hundreds of thousands of starving angry war battered people, Germans, Iranians, Slavs, and many more in Gaul. And their response was a resounding “Meh”.

For two years the barbarians went unopposed across Gaul as the Imperial government pretended the problem didn’t exist. They raided farms for food, armories to defend themselves, and they took any gold item not nailed down. As the peasants abandoned the countryside, the cities became inundated with Gallic countryfolk looking for legions to defend themselves that didn’t exist. Many formed robber bands called Bacaudae which, too often, began acting like the barbarians too. The Galic nobility did not want to deal with this problem, but now their assets were at risk, and they needed to find a solution. And Rome wasn’t coming to save them. So who would?

For the past century, the very Romanized Franks had integrated into the local legions and police, and the Nobles began to look to these half- Romans to defend themselves. The success was mixed, but these Franks proved more loyal than the Romans. That got the Aristocrats of Gaul thinking. This was the first time they realized Rome wasn’t coming to save them. They needed a way to deal with problems on their own. And, while there are no recorded declarations of independence from the Nobility of Gaul, this was the first sparks of independence. Not in declaring independence itself, but in self defense. Private armies became key to Gaul’s defense.

In these early chaotic years, not much thinking or planning went into these responses. The Gaulic Nobles simply threw money and men at the problem. Hire the half civilized Franks to fight the uncivilized horde. But this was not a winning solution, and after many betrayals and ad-hoc defenses, Gaul began to crumble under the weight.

But why didn’t Rome respond? Why did the Imperial government ignore the largest incursion of its territory in recorded history? Why didn’t they care? Historian Charles Paul Minor, in his 1976 thesis, attempted to answer this question by looking at it through the framework of assets. He notes:

The aristocracy of the Western Empire was not, however, one unified body. The two major aristocracies the Gallic and Italian, had remained on generally amiable terms, but had never merged into one group—one imperial or Western aristocracy. The Italian aristocracy had jealously retained preeminence in the West and had continuously held a disproportionately high percentage of the imperial offices. The praetorian prefectures, the Italian and African provincial governorships were almost exclusively in the hands of the Italian nobles. Even the provincial governorships of Gaul were generally held by Italians. The only Gallic families to regularly reach high imperial office during the late fourth and early fifth centuries were the Firmini-Magni-Ennodii and the Claudii. A separation between the two aristocracies can also be seen in a comparison of their land holdings. The Italian nobles owned vast estates in both Italy and Africa, but apparently little land in Gaul. The majority of the estates of the Gallic nobles appear to have been in Gaul itself, with some holdings in northern Italy, but apparently few if any in Africa. This distribution of land holdings was to influence greatly the relative viev/points of the two aristocracies pertaining to imperial policies, and was to become increasingly important in the fifth century.

Simply put, the Italian Nobles didn’t stand to lose anything from the rape of Gaul. They didn’t own any landed assets. They didn’t suffer any losses. Gaul had built generations of independent wealth in Gaul, but it was independent wealth. Other than the barely collected taxes, Rome didn’t benefit from this wealth. Without landed investment, Rome felt it had nothing to protect. There are parallels here with our own Southern border. Does the federal government even own any assets in Texas? If not, why act?

Whether or not the Gaelic Aristocracy was aware of this problem at first isn’t clear. But Gaul wasn’t alone in its suffering. As the Barbarians began to spread out into Iberia and Britain, the locals there faced the same problems, though again Rome only bothered when its Italian aristocracy’s assets were threatened. This incursion exposed the divide between the aristocracies of Gaul and Italy. The Gauls had to elect to find from their own a champion to organize their own response. Gaul, in these early troubled years, found itself functionally independent, and didn’t know how to deal with that.

The soldier, Claudius Constantinus, arose in Britain to defend against the Saxons, and once stabilizing that province, offered aid to the Gallic Nobles. They gleefully agreed to the support, and put him in charge too. Reminiscent of the Gallic Empire during the Crises of the Third Century, this little coalition of provincial militias and federated Franks and Goths managed to somewhat take hold of the situation. However, a curious thing happened when they started succeeding: Rome Sent a Legion to destroy the Usurper. Charles Minor notes this as a key turning point for the Gallic Nobility. The Gaelic Nobility became aware that Rome only cared about its primacy, not its people. They realized Rome didn’t give a damn about protecting them from barbarians. They did, however, give a damn about potential threats to its throne. Because sure enough, Constantinus began to eye Italy as his next conquest. He writes:

It is interesting to note that the imperial government at Ravenna had made no effort to oppose the invading barbarians, but was quick to confront a usurper. The authority of the imperial court at Ravenna was apparently more important to that court than was the safety of Gaul.

So, if you’re wondering why our own government cares more about the governors of Texas and Florida taking on their own problems rather than the open border causing the problem, there’s your answer.

By 410, the barbarian hordes had reached Rome and sacked it (It was fiery, but mostly peaceful, with only one confirmed death). Rome finally had figured it had to deal with the problems on the border now that the Italian’s landed assets were threatened. By 418, stability had somewhat been restored, and the Gallic Nobility pushed for greater autonomy to deal with problems in the future. Rome settled the Visigoths in Aquitaine to put down the Bacaudae mobs, and it was decided to form a Council of Gaul at Vienenisis to take petitions from the Nobles. The loyal Franks were granted the right to form legions and began acting much like the Army of Gaul. The Gaulic nobles also formed a Tribuni et Notarii, which was a kind of parliament for Gaul to govern its own affairs alongside the Council of Gaul to petition the Imperial Government. However, and this is important, NO gallic noble served in high imperial office from 414AD to 448AD. For siding with a Usurper, they were barred from the Imperial government, and could only govern themselves locally. There would be no concessions at the imperial level.The elections would be fortified thereafter.

However, the Gallic nobles made do with what they could, and they now had official bodies to begin to strategize for their own defense. This was the first time Gaul’s noblemen had tasted what independence might feel like, even if it was through controlled containment.

(The Franks by this time had been civilized, wearing Roman styles equipment. This would be their appearance from the 5th century through the 9th)

Throughout these 34 years of containment, usurpers did rise and fall, but they always fell. Somewhere along the line, however, a petty officer by the name of Aetius began to raise through the ranks. In his youth he had been held hostage by various Barbarian kings settled in Gaul, and had befriended many of them. When he became a Knight of Gaul, A Palatanii, he began to recruit his loyal inner circle from the Goths and Huns. Romanizing them as he trained them in the Roman way. He showed potential, and eventually worked his way through to the rank of Comes, or Count. Count Aeitus had spent his youth fighting remnants of the Bacaudae, rebellious barbarians, and even served under one of Gaul’s many Usurpers. He knew Gaul, though he was not Gaulish himself. He knew how Gaul worked. The Son of an Italian nobleman, he saw great potential with what was once again becoming one of the only stable parts of the Empire.

But he did something no one in Gaul had done before: He began to network and build a brotherhood while the rest of the empire stagnated. He also did something that neither the Romans nor the Gauls had done: He patronized the Gaulic nobility. He handed out benefits to friends, and he punished enemies.

But the question remained, how was he going to wrestle Rome’s institutions from the Italian Nobility? Well, remember those friends he had made while a hostage of the goths? Rome at this time was ruled by Empress Galla Placidia, who was the wife of King Adolf of the Visigoths. It was a very strange Dynastic Union, but one Aeitus could network with his childhood friends. Fate also smiled on him when the Imperial Government lost control of Africa to the Vandals. Without African Grain, and losing their estates in Iberia to the Goths, the Italian Nobles now had few assets outside of Italy, while Aeitus had assets across the west. They were weak, Aetius was strong. He had Gaul’s Farms, Gothic Spain’s soldiers, and friends in Italy. He networked while the rot ate at the Empire such that by the mid 430s, he had risen to the rank of Master of Arms of Gaul and had managed to get the Empress to grant him the rank of Patrician, and use his Gothic allies to promote him through the ranks so that he became the defacto ruler of Gaul.

Once he had that political capital, he didn’t spend it drinking wine and feasting on the corpse of the Empire. First, he stripped the tax free status of the Italian nobility to increase his coffers. Then, he started replacing the judges of Rome with his allies and instituted laws that meant when a Gaullic nobleman was sued, the case had to go through him first, before being handed to a judge of his choosing. These reforms were not neutral. He wasn’t trying to create neutral institutions or equality with the Italians. He was playing for keeps, and he was keeping at heart his allies. Something Republicans could learn from today. He greatly enabled the Gallic Nobility such that they now ran the institutions of Rome. For generations Rome had used the competent class of Gallic nobles as the middle men, but now it was the Gallic Nobles at the top.

Do note, this took decades, not some brief 4 year term. He had made Gaul the center of the Empire. The capital was now in Gaul. The recruitment base in Gaul. The Institutions in Gaul. It was now the Gallic Empire proper, not that spinoff series in the 3rd century. Things like this take years of planning to accomplish. Don’t fool yourself that it can be done in 4-8 years. This was decades of work. And that’s the kind of mindset you need when networking in decline.

"The Fruits of Gaul”, a rather curious relief celebrating Gaul’s intellectual accomplishments. Noteworthy for their rather abstract collage style.

We can get a clue into the mind of Aeitus in some of his letters and the letters of his friends. One of my favorite letters is the call to arms that the Romans sent to the Visigoths to fight Atilla when he invaded. You may recall he had made friends in the barbarian courts in his youth, and he had continued to patronize those friends. This letter, written by either Aeitus or his friend Avitus, was written to his childhood friend, now King of the Goths, Theodoric:

Bravest of nations, it is the part of prudence for us to unite against a lord of the earth who wishes to enslave the whole world; who requires no just cause for battle, but supposes whatever he does is right. He measures his ambition by his might. License satisfies his pride. Despising law and right, he shows himself an enemy to Nature herself. And thus he, who clearly is the common foe of each, deserves the hatred of all. Pray remember--what you surely cannot forget--that the Huns do not overthrow nations by means of war, where there is an equal chance, but assail them by treachery, which is a greater cause for anxiety. To say nothing about ourselves, can you suffer such insolence to go unpunished? Since you are mighty in arms, give heed to your own danger and join hands with us in common. Bear aid also to the Empire, of which you hold a part. If you would learn how such an alliance should be sought and welcomed by us, look into the plans of the foe.

[Likely penned by Aeitus himself, or future emperor Avitus, who was a personal friend of the Visigothic Royalty]

Romans, you have attained your desire; you have made Attila our foe also. We will pursue him wherever he summons us, and though he is puffed up by his victories over divers races, yet the Goths know how to fight this haughty foe. I call no war dangerous save one whose cause is weak; for he fears no ill on whom Majesty has smiled.

[Likely penned by Theodoric I or II, friend of Avitus]

But there’s something more Aeitus did that has gone mostly undocumented by historians. Aeitus was not dumb. He knew he wouldn’t be around forever, and it could all come apart if he was killed or replaced. So he created a new institution to ensure these policies would continue after him. He formed a secret society called the Coniuratio Marcelliana, or, the Oath of Mars. This Secret Society was tasked with preserving the Gaul First movement Aeitus had instituted. He filled this society with proven loyal Gaels, Goths, and Franks, and tasked them to share resources to hold control. Mutual Aid between competent people. One of these members, Sidonius, was a Roman Senator from Gaul, Patrician, and close confident. Just what the Oath of Mars was and who was a member is mostly lost to us, but we have some mention of it in Sidonius' works. Nonetheless, historian Edward Stevens writes his frustrations with the secrecy around the Oath of Mars:

Sidonius himself described the oath as in his poetry, very cryptically, as follows:

And when the Oath of Mars sought to seize the diadem while it was simmering, he had presented himself as a standard-bearer for the noble youth in the faction, a man still new to old age, until eventually, because of the daring exploits of his fortunate audacity, he gave a gleam to the gaping chasm of an interregnum in his obscure lineage. For when the court was vacant and the republic in turmoil, he alone was found who, before many months had passed, dared to ascend the tribunal of illustrious powers to administer the Gauls with fasces rather than codicils, having barely completed the term of his final military service, following the manner of paymasters or rather legal advocates, whose actions end only when dignities begin.

-The Epistle of Sidonius

You can get from this that the Oath was composed of Sensitive Young Men eager to work together to aid each other in this enterprise of preserving the Empire. But I have some bad news. Eventually, this movement did lose power. It was the end of the world, after all, and fighting over ashes wasn’t the most productive thing to do. Throughout the 450s as the Italian nobles tried to wrestle back control of the institutions of the crumbling empire, and incompetently fumbled everything into collapse, the Oath was forced to reconsider if preserving the Empire itself was the best means to preserve Gaul.

They ultimately decided on a change of policy. One that would ensure that while they wouldn’t save the empire, they would outlive it. They went shopping for allies. Eventually they would opt to use the faithful Franks to their advantage, and when the Romans no longer had the power to maintain themselves, the Franks would go on to take Aetius’ accomplishments as the foundations of the nation we now know as France today.

Historian Charles Minor concludes:

It should be noted that members of this network of interrelated families not only held three praetorian prefectures of the Gauls, one praetorian prefecture of Italy, a consulship and two patriciates in the years 439-454, but an additional eight praetorian prefectures of the Gauls, an urban prefecture, consulship, patriciate and the emperorship in the twenty-two years after the death of Aetius. This network of families rose to prominence under Aetius, supported his policies, and continued to hold high Imperial office until the fall of the Western Empire.

All this is to say, even here, at the end of all things, you don’t have to give up. It takes time, but the loyal friendships you form today can and will be there to support you tomorrow if you pick them right. These Friendships might not be able to save America, but they can outlive it.

You can start forming brotherhoods that will outlive the ashes you live in now. And if you end up like the Oath of Mars, you may even build something that becomes a Spring after this Dark Winter.

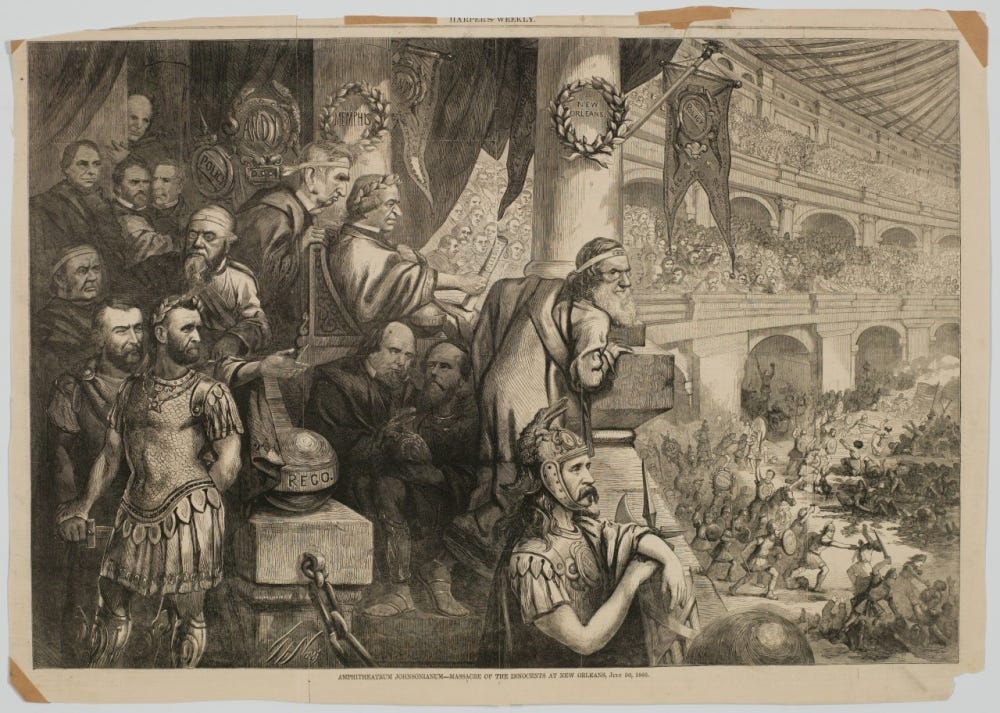

An amusing Roman style drawing of New Orleans, in America.

Borrows from a previous article:

The Oath of Mars

Dear reader, I want to tell you a ghost story - a mystery from the end of Imperial Rome. A mystery passed down to us by the very barbarians that helped cause said end. However, it pertains not only to the ghost of a man - in fact, several men - but the ghost of an idea. As you’ll soon see, were it not for the studious work of some few men, said ghost st…

And the Roman capital of Gaul was located in Soisson, with Syagrius falling to Clovis in 486, so that though the families in support of Gaul had wished to build themselves a base of power, they were usurped and conquered by Clovis who used their lands and those of his own people as a foundation for his own kingdom.

That said, any who joined him were accepted as Francs, so that there was little in the way of conflits between him and the local people as he in some ways assimilated to them rather than the other way around.

Excellent article, I always liked Aetius and found that I could not understand why historians hated him, he beat Attila! He drove the man back! Shouldn't he be praised for this and for having attempted to save the Empire? And yet, most English-speaking historians I've met hate him and consider him a buffoon for some reason (saving a few here and there). Or they describe him as 'tedious to study' never understood that.

Twas a pleasure seeing you in person, glad I can read this over once more and absorb some fascinating history on top of the lessons it holds.