Remanence

How do you know what was there?

When everything falls, what is left as a remembrance? How do you know anything was there? This question intrigues me, professionally as an architect-in-making, but also for the verification of history compared to myth. Modern man knows Troy was real, because he found the ruins. Modern man doubts Atlantis was real, because he hasn’t found ruins. I am ever-curious if what I build will survive, or be turned to myth. Everything turns to dust eventually, so perhaps myth is as much our future as our past.

The idea of “Ruin” in art goes back centuries. Germans were always curious of the Latin structures that dotted the distance from their castle keeps. You will find ruins painted into their art in perpetuity. Classical writers, too, write of the ruins of Egypt. The Pyramids were already ruins in the days of Caesar, after all. And they also marveled at Babylon’s dust they found in their conquests. Of course, such even more ancient people knew of ancient ruins from before they stood. It is said the story of Atlantis comes from Egypt, who record that mythical empire as the ancients of their own standing. The world’s oldest museum was founded by Ennigaldi-Nanna, a Babylonian princess. She founded her exhibit in Five Thirty BC, even labeling artifacts with supposed dates and origins in a very familiar style we would recognize today. Some of her museum labels are still in readable condition today. They featured multiple languages inscribed in cylinders for different tourists who may stumble into her little gallery. A tourist would simply grab a cylinder, align the clay to the row they could read, press and roll it, and have a translated inscription for their curiosity. Essentially a very primitive version of those multi-language audio tours which you may find in any continental museum of Europe today.

A simple plan of her palace reveals just how many galleries and spaces she had for her museum. To find something preserving things from ever-more older than itself is quite a treasure-find indeed - at least, were the museum to have survived in better conditions.

However, less found in art and literature is the conceptualization that your own works may one day be ruins too. To this day I have found no ancient who envisioned their own works as ruins for future generations. Only their commentary of the ruins in their day. This conceptualization of your own demise seems rare.

You will then be unsurprised to imagine most of these concepts emerge out of the 1950s, when the idea that civilization could end became very real in the Atomic Era. However, you may be more so surprised to find there are a few earlier incarnations of this concept.

Joseph Michael Gandy’s 1830 painting, shown here, depicts the ruins of the Bank of London. The perspective is that of some unknown future explorer of the ruins of London. The painting, so much that I know, is the earliest depiction of a westerner imagining their own decline and fall. Envisioning your own Imperial Capitol in a state of ruin - at it’s height in history, no less - seems to me a uniquely Anglo-Saxon invention. I have searched, but I have found no paintings nor books which can be grouped with Gandy’s works, which appears to be the birth of the “Post Apocalypse” genre in art. Below, is another of his paintings, showing a ruined Rotunda of a future London.

I find it troubling that no one understands the incredible accomplishment this painting represents. It is the understanding that your Empire is but one in history, and not likely to outlast any of those in the past. The closest I have found, is that famous poem by Shelley, “Ozymandias”. Written only twelve years prior, I am curious if Gandy took any inspiration. So much I can tell, the 19th century features only one other work of Post-Apocalyptic art: Gustave Doré’s “London: A pilgrimage”.

Doré says his work was inspired by Thomas Babington Macaulay, who in a passage on the longevity of the Catholic Church wrote:

…She saw the commencement of all the governments and of all the ecclesiastical establishments that now exist in the world; and we feel no assurance that she is not destined to see the end of them all. She was great and respected before the Saxon had set foot on Britain, before the Frank had passed the Rhine, when Grecian eloquence still flourished at Antioch, when idols were still worshipped in the temple of Mecca. And she may still exist in undiminished vigor when some traveler from New Zealand shall, in the midst of a vast solitude, take his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St. Paul's.

Doré’s New Zealander on a journey to the ruins of London for Architectural inspiration is deeply meaningful to me. The ruins show the end of civilization in Britain. But the scholar from the south shows that British civilization would continue on, elsewhere. Like his Anglo-Saxon ancestors who moved onto the island from Denmark, he is the product of moving to yet a new home afar.

These works bring me some kind of bittersweetness of the soul. I know I live at the end of my civilization. I know these caves of steel will be dust sooner rather than later. But I’m not there yet. I’m still in the afterglow. And that makes me wonder what once glowed before me…

The average American believes the Eastern Native Peoples of North America never built a civilization. The best they accomplished were some mud huts and flint arrowheads. But how do we know? Most Americans can’t point to anything they would call civilization, I suppose is how it’s assumed. They think that because they cannot see ruins of aqueducts and castles, that there must never have been anything more. This is a common theme whenever people are asked what they know about the deeper lore of the land they live in.

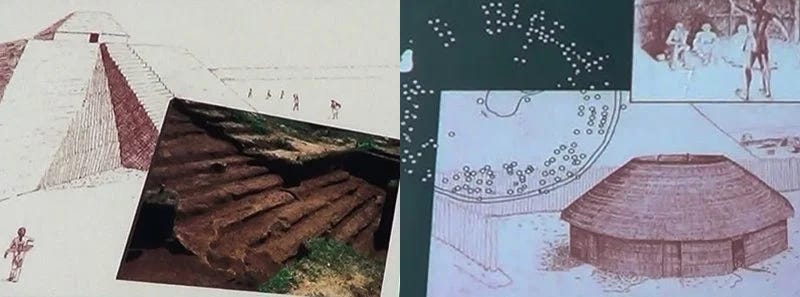

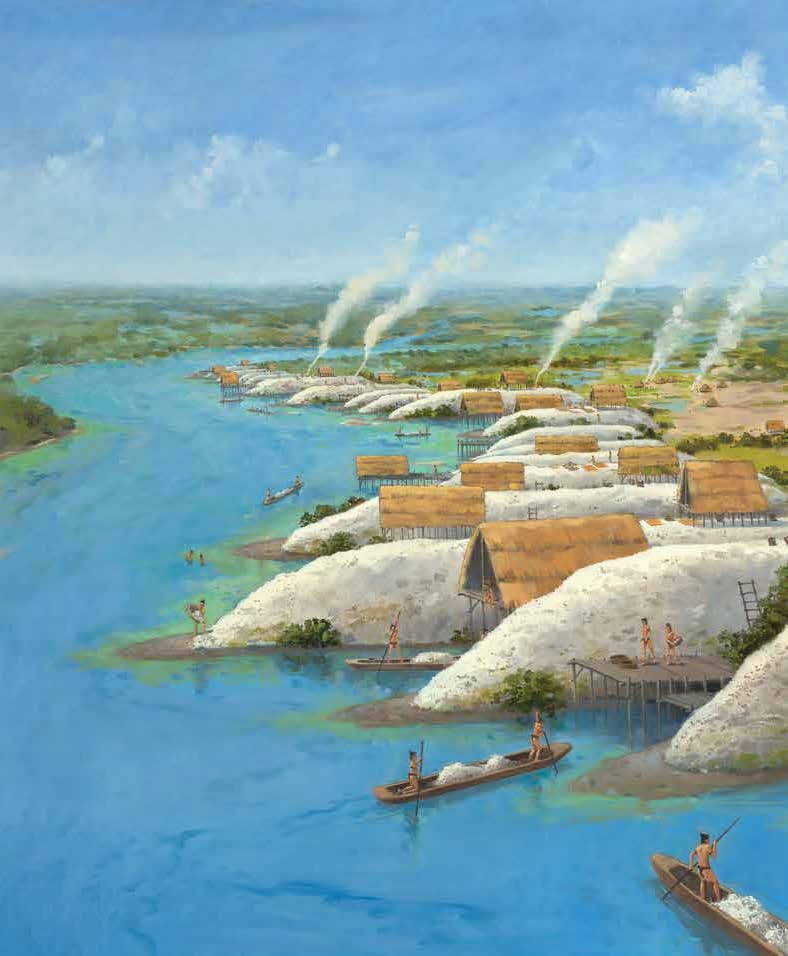

If you’ve gotten a little bit of an education, you may have heard of the Mississippi River Civilization, though you likely haven’t heard much more beyond the mounds they left behind. In fact, they were city builders. A rather accomplished civilization in their own right, though their cities were born, lived, and extinguished long before an Anglo-Saxon ever planted the Union Jack on these shores. Their heyday was probably around the time William the Bastard took the Isles back into the threshold of Papal Authority.

It’s really only been in recent years that this civilization has been more thoroughly investigated, and as such only recently that any real artifacts were found a few feet below the fields of America’s heartland. One wonders what may have been found earlier by farmers that was disregarded as little nothings. Etowah, show below, was a fortified city-state that collapsed in the 16th century. Stretching Two Thousand Feet by Twelve Hundred Feet, it was just a tad smaller than New Amsterdam’s original Wall Street perimeter. It’s possible its last inhabitants may have greeted Spanish missionaries. If it was documented, it is likely lost in myths of golden cities. Perhaps mistranslation of golden fields of corn.

The Etowahans were not mere flint-grinders in mud huts. They had a complex metallurgy culture that shaped and cast copper into icons of various deities. More complex than the ordinary idea of what a Native North American was capable of.

In addition to Copper icons, they appear to have experimented with copper architectural veneers. Here’s a relief that may have formed either a wall or floor tile pattern

In addition, Copper and metal musical instruments have been found, most famously were bells which seem to have been sized for various frequencies. Do note the seam line suggesting a sophisticated level of casting assemblages and not just single-cast objects. The ability to smelt multiple pieces together is actually quite a technological jump from single-cast pieces.

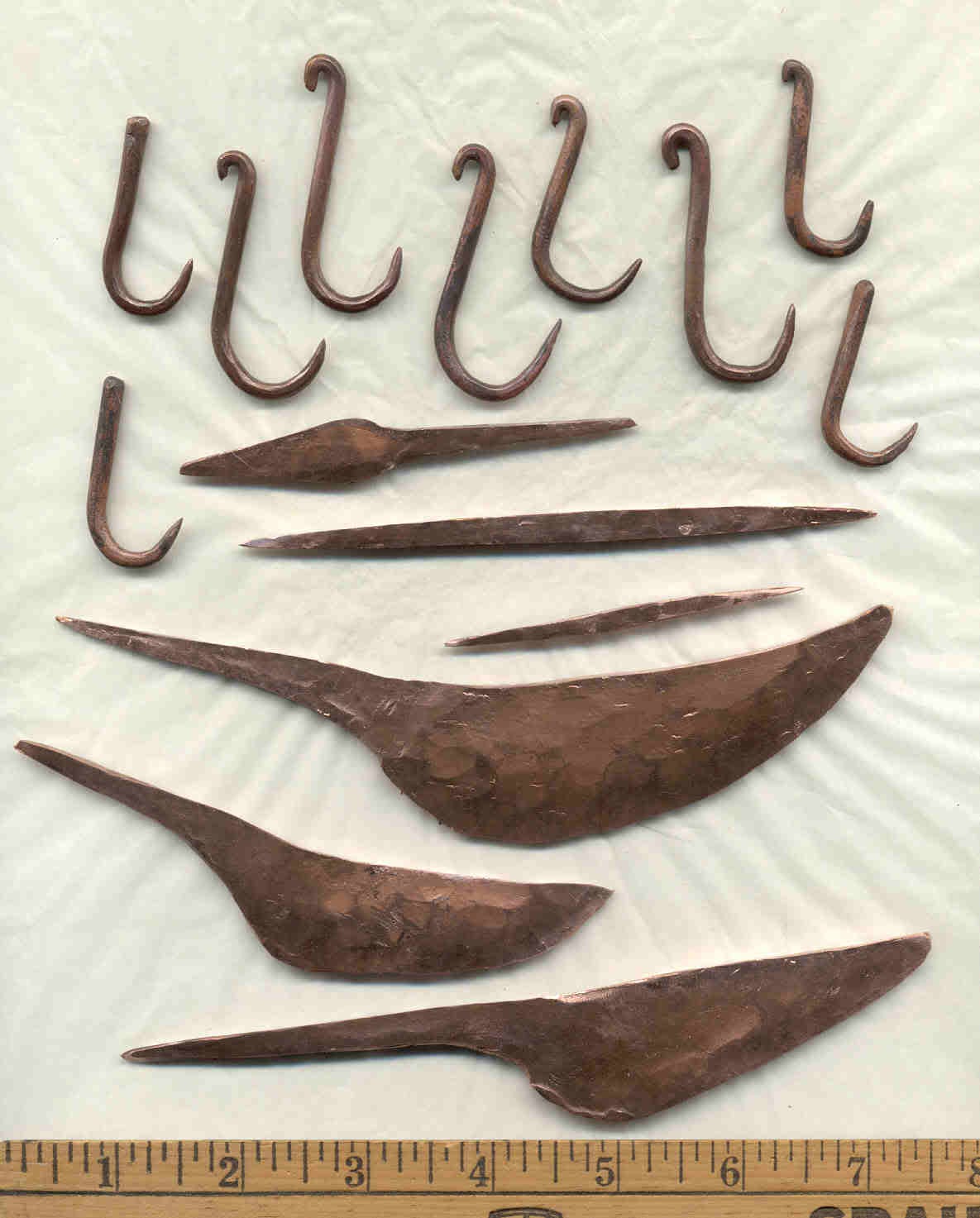

And of course, copper weapons and tools have been found plentiful in the region.

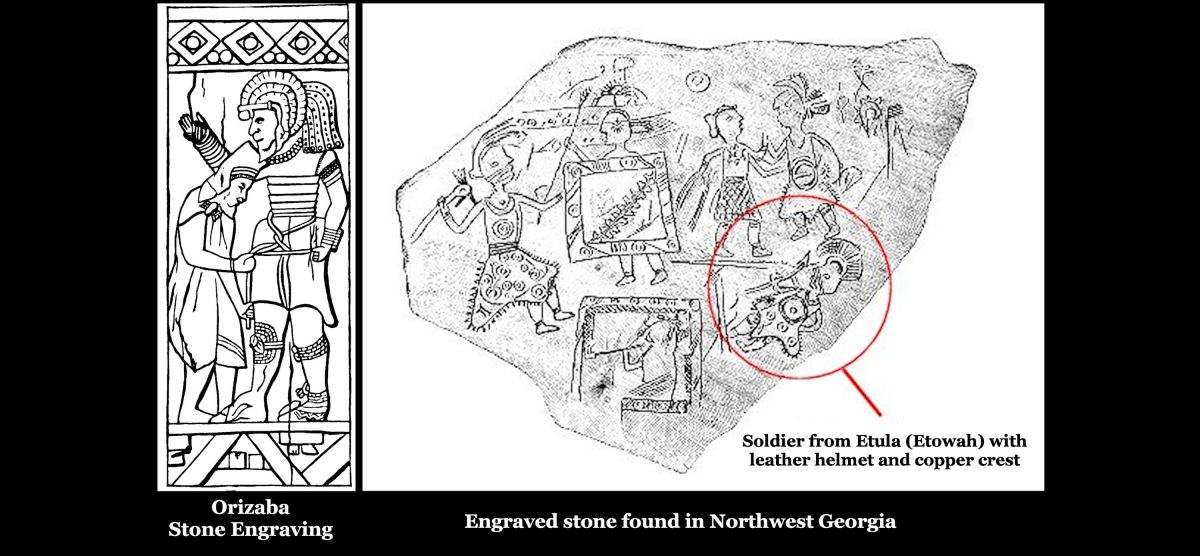

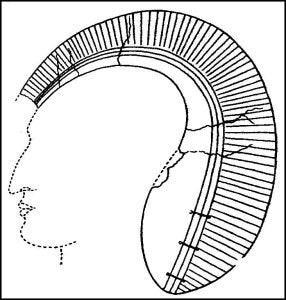

Above here, you can find a depiction of their warrior and priestly casts. It appears the Etowahans were a bit more advanced than the Aztec or Maya, developing proper metal shields and helmets, along with a rather curious mohawk copper helmet.

A number of blade weapons have been found as well, dispelling the common myth that Native Americans never developed swords. Albeit these were flint. I have seen copper blades elsewhere.

The Etowahans also smoked, of course. We know, because a number of pipes have been found on the site as well

Within the city walls themselves, the architecture was a step above the usual teepee and mud huts often assumed of native peoples. Straw roods, likely finished floors, and larger religious temples all show likely placement in the city. it doesn’t appear they had many roads, but they did have their comforts all the same.

It’s unclear if Etowah was a lone city state, or part of a broader city-state empire or culture. Such things are lost to history. But many sites have been found in the region, including the Jonesville Earthworks in Louisiana, and the more well known Cahokia ruins, who’s cityscape featuring a ball game arena and a pyramid introduced this segment. Artifacts from these sites seem a tad more archaic, but still rather detailed with technical abilities.

Perhaps the most curious find are what are known as “Black Drink Cups”. North America has no native coffee beans, but it does have the Yaupon Tree, which has a decent amount of caffeine in it. So we know the residents of Cahokia enjoyed a nice cup o’ joe in the morning. Their rich schemes suggest they also enjoyed waking up to bright colors as well.

Cahokia dates to about two hundred years before Etowah, and passed into abandonment about a century before Etowah did as well. It’s likely they were trade partners, although they appear to have maintained distinct cultures. One focused on copper, the other on stone. And my favorite stone artifacts of the Cahokians, are their depictions of faces:

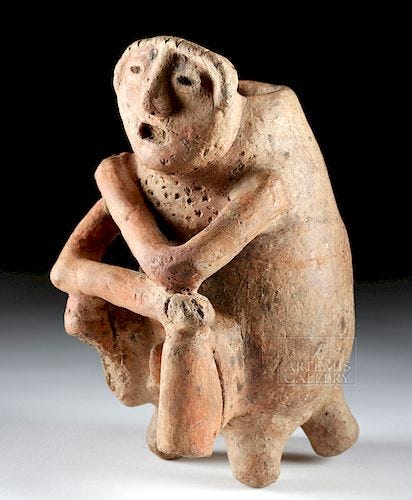

Although by no means complex in detailing, they somehow have a depth of personality in them that seems more than mere cheap dolls for children. There’s the elderly stair into the void. And another, with deterministic, focused anger.

These statues lack proper proportions and almost appear to be comical. Perhaps they formed some kind of game or theatre piece, Or perhaps memorials of great warriors? We don’t have any records of the Mississippi Civilization. No historians wrote down their lives. We don’t know the names of these gods and kings. We don’t know what deeds they did. We only have their faces to ponder what they saw and felt.

Perhaps you will find it interesting that these effigies, as they are known by, are all smoking pipes - It being one of the things that sets Cahokia apart from Etowah. The Cahokians detailed their pipes, the Etowahans preferred utility over beauty. Something akin to the Spartan-Athenian relationship.

I very much enjoy reading about these little-known cultures under our feet here in the States. It’s easy to imagine there’s just mud and bones and that’s it, and when we are ruins perhaps those after us will assume the same. Yet if you look close enough, you may find a whole chapter of history, lost until you turned the page.

There’s one passage by a German Priest visiting Pennsylvania that’s often struck my curiosity. Gottlieb Mittelbergers Reise nach Pennsylvanien im Jahr 1750. Gottlieb describes a rather curious claim. I will let an English Translation of his diary describe it for you:

I have no way to verify Gottlieb’s claims. The linguistically attuned will know Jesus’ name is Joshua and may brush this off as merely an old church from a century of colonization. Yet we really do not know. And one thing that worries me, is this common theme in many early colonial diaries that they were taking apart ruins to build America’s first cities. I sometimes wonder how much of what was we recycled in our own early buildings. How do we know what we live in was originally our people’s? How could we know? Would there be any way to test?

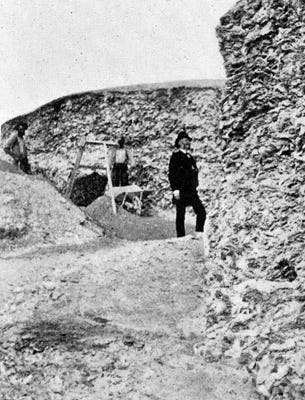

In Maine, we know something of a people existed along the coasts. Vast foundations made of shells and wood. We know they existed, because people described them. But we cannot find them anymore. Because, as it turns out, Shells make great fertilizers. So the early colonists burned these foundations and spread them over their crops. Luckily, some were still around to be photographed before they were all destroyed.

Many of these foundations could support large multi-story structures. They were tall, and likely built to persevere against tides. The natives would live atop them and catch things in the troughs for food. Many of them appear rectilinear in form, suggesting some sense of angled construction.

I’m told many of these sites may have inspired Lovecraft at one point. Though by his time they would have all been destroyed. I imagine he had only photos like these to ponder them, likely inspiration for his science fiction.

Along with these, there’s evidence of pottery and other artifacts, although finding anything in an area prone to coastal erasure is rather difficult and an almost impossible task…

… Most of that impossible task was risked by Professor Edmund Von Mach, by the way.

The best idea of what this settlement likely looked like can only be garnered by similar architecture found more south in Florida. As that’s a different climate, it can’t be assumed to be a perfect replica. But near enough to imagine.

Relics of this costal people can be found also in the Carolinas, where they developed ring-shaped artificial islands for their lifestyle. They can still be visited today.

We do not know much about these coastal peoples. Interesting enough, there’s a bit more detail from the Vikings, as they recorded a few bits of information about their abilities. We know they had large ships with which they could crew a few dozen people on. We also know they had ballista, as the Vikings record dodging explosive clay shells that could sink their longboats. We thus know they were quite an accomplished people in terms of military technology.

I have many more examples of Native American architecture. One day I want to write about the Ruins of Raqchi, an enormous temple complex practically unknown to most Americans. Ruins I am only privy to know about thanks to my profession, and friendship with Latin American architects.

But these suffice for my thoughts of the day on Remanence. And I hope you now understand just how much is under your feet, and perhaps consider what you are leaving for someone else’s feet to stumble upon.

Most of these sites are less than a Thousand years old. Most became ruins in mere decades of abandonment. And most are cultural dead ends. They told no one their beliefs. They taught no one their crafts. They were born, lived, and died in bubble universes that only God can perceive.

I wonder often about remanence. What will survive of this generation? Most of our culture is digital now. One solar flare would erase nearly everything we’ve made. But would we miss any of it? Our stories aren’t that great, our music isn’t that interesting, and our artifacts are mostly sex toys and birth control along with the usual cheap shit mass produced all around. Our art will likely be confused for animal scratch marks. Our books are no longer printed to last centuries. They would turn to lose threads and shredded papers within a decade after a collapse. Our food is GMO and often no longer able to reproduce on its own. So our crops would mostly disappear within a generation. Gas goes bad in a few weeks, and cars turn to rust from salt and water. All of this feels like stagnation before the decline, and not much survives stagnation. Almost all of Rome’s famous buildings you can think of were built within a few decades of Augustus’ life. Nearly nothing remains from the Republic, and nothing from the late Empire. Rome’s definitive iconography is nearly entirely early Empire and that’s it. That’s what survived. In a thousand years of Western Roman heritage, only a few decades of culture endured to become the cultural background of the west.

What of us? What if the only things that survived to tell our tale are a handful of decades before the 1970s, and that’s it? Would the average future inhabitant only know about Lincoln to Nixon? Would anything else survive? What will be our remembrance?

I ask you, too. If you know no one is going to remember your super-cool frog and npc meme, why are you wasting your brain power making it? Why are you coping? Reality is folding in on itself around you. Are you going to spend this time wanting an upvote? Or making sure you are remembered?

Imagine if today you died and your remembrance began to decay. What would endure? Anything at all? Would anyone know you ever existed?

What are you going to replicate for people to remember you by?

What will you protect and teach others to remember us all by?

Will future artist visit your ruins on pilgrimage?

Will future writers record your wit for the ages?

Are we even worth remembering?

September 28th, tomorrow as of writing this, is Shemini Atzeret. A little known Jewish holiday celebrating the remembrance of the Torah as the foundation of the Jewish Faith. Though I have no more living Jewish ancestors to celebrate that, as a Christian I hope to remember Christ’s impartation of wisdom every day. That - the realm of faith - I have and am eager to preserve for remembrance. But I’m also an English speaking American. I do wonder if there is anything worth remembering. What’s the line from stable culture to dying culture? When did we go wrong? Was it the whole enterprise? Or was it some wrong turn we took a century ago? Should we go back? Call it quits and call the whole enterprise of the American experiment a failure? Or is there a future to drive towards?

Remanence is something to consider. Consider these things deeply, as there likely isn’t a great deal of time left to.

So when are we getting "Luthemplaer's Secondary America: the First Fall of the West"? :P This was awesome to read!